Don’t Judge a Book by Its Cover

Portrait image of Bernard Voïta

Portrait image of Bernard Voïta

With its meticulously constructed images, visual puns, historical references and a unique take on photography, Bernard Voïta’s art has evolved as a highly distinctive view of what we call ‘reality’. Currently, his work is on view at Fotostiftung Schweiz in Winterthur.

Never judge a book by its cover, they say. But in the case of Bernard Voïta’s stunningly beautiful catalogue ‘Melencolia’, published to accompany the namesake exhibition at Fotostiftung Schweiz in Winterthur, it may be fair to make an exception. For in this case, the cover isn’t a cover but a first page, made of exquisite brown recycling paper, like much of the rest of the book. And on this first page there is an image: a simple drawing that shows six people, each touching, feeling and palpating a massive elephant in their midst.

As Voïta writes in a small text in the book, the image refers to a version of an age-old story or parable. He heard it from Chérif Defraoui, one of his teachers at École supérieure d’art visuel in Geneva, where he studied in the 1980s: Several blind people have been asked to describe the look of the animal before them. Of course, they come back with utterly different ideas depending on which part of the animal’s body they touched – its long and flexible trunk, large ear, massive legs, or thin and bristle tail. And, of course, they start to fight over their conflicting views.

‘Our view of reality is necessarily fragmented and dependent on perspective.’

Our view of reality – and that is the story’s takeaway – is necessarily fragmented and dependent on perspective. The same thing can look different when perceived from another angle and even combining all the separate views into one doesn’t necessarily add up to an accurate bigger picture. As Voïta explains, the same is valid for photography, this seemingly all-so-objective medium he works with the most, even though he would not call himself a photographer. This parable truly serves as a perfect entry point into the wondrously poetic and, at times, fantastical and eye-rubbing world of this artist, who, since the late 1980s, has perfected his very own take on perspective, perception and our expectations on reality, on fragmented views and the endless attempts of making sense of what we see.

Pre-Produced, Not Post-Produced

It is fair to say that the 15-piece series ‘Melencolia’, 2014–2017, which is on view in its entirety at

Fotostiftung Schweiz in Winterthur, somehow presents the essence of Voïta’s approach – perfectly

balanced in its effects and present in the moment, yet highly conceptual and imbued with carefully

placed references;

almost cautious in its attitude, yet conscious and visibly confident; and, last but not least,

beautifully installed, including remnants of other exhibitions that had happened in the same room

before.

‘Disorientation here is the effect of a rigid arrangement.’

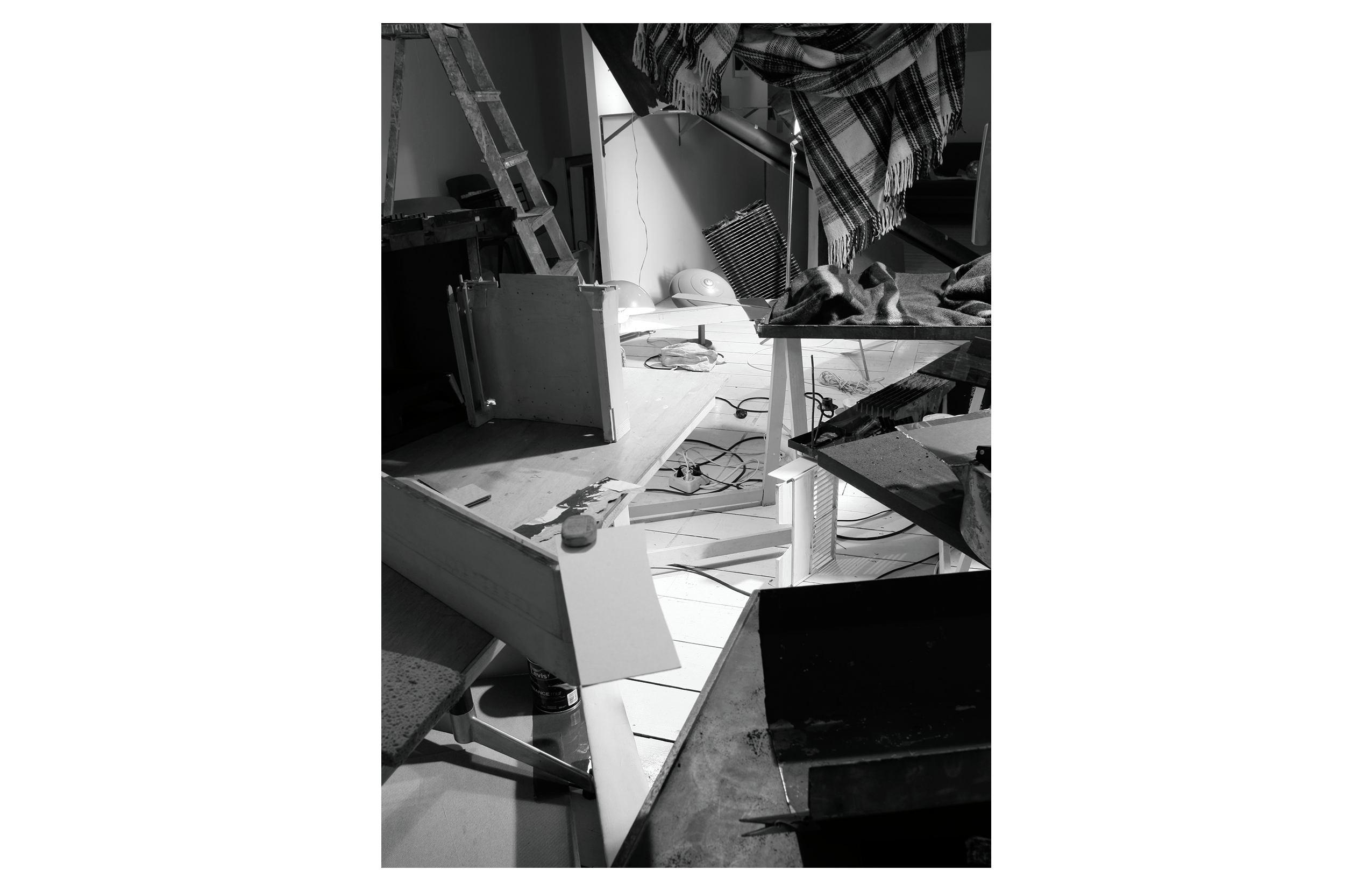

Seen from afar, the large-scale photographic works themselves, named after Albrecht Dürer’s famous 1514 etching ‘Melencolia I’, all seem to form clean geometrical patterns in black and white. When coming closer, though, they reveal a strangely balanced mess, made of everyday objects in the studio that have been meticulously arranged to cast sharp shadows, making up the fractal-like patterns. All of a sudden, things seem to fall apart in front of your eyes. Disorientation here is the effect of a rigid arrangement.

‘Melencolia IV’ is one work from the series that exemplifies the methodology applied throughout. The single elements of the work, which is part of the Julius Baer Art Collection – a blanket, a ladder, a table, a table lamp, wires, a paint pot, and many other loose parts – are meticulously placed to form order out of the chaos and create an elaborate play of light, shadow and perspective. Voïta’s images may look ‘post-produced’, much as if they had been collaged on the computer, but they are not. They are the opposite: ‘pre-produced’ in a detailed process and only visible to the camera.

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Melencolia IV’, 2014, inkjet print on paper, 180 x 130 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Melencolia IV’, 2014, inkjet print on paper, 180 x 130 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Photography and Objectivity

Behind this is an approach to photography that Voïta has perfected since he first came up with the idea

in 1987 for his series ‘Antichambre’. Instead of using the camera to depict the world objectively, Voïta

flips things around, arranging and thus inventing a world that only exists ‘for’ and, more importantly,

‘in’ the image. The images only start making sense from the singular perspective for which the room in

front of the lens has been arranged. What you see is no objective view of the world, but rather a highly

subjective one. The separate details, the fragments, may well have a clear referent in the outside world

– but the image as a whole does not.

‘Photography, with its presumably privileged and objective access to reality, may have been a historical anomaly.’

Another series by Voïta, which is similarly part of the Julius Baer Art Collection, makes this turn towards the seemingly objective qualities of photography even more apparent. For ‘Camera’ from 2003, the artist technically followed the same approach to arranging and organising things for the camera’s lens but added a decidedly self-reflexive twist. Here, the final images do not form abstract patterns but rather concrete ‘objects’ – various models of photographic cameras. Nothing is as it seems; the multiple dimensions nestled in each other feel like collapsing. In the end, what appears to be a real camera isn’t even a model but a chimera created out of light and perspective. Fittingly, the title is a hidden play as well – hinting not so much at the photographic apparatus pictured as at the room (a ‘camera’ in Italian) of the studio itself, which is what makes these images possible in the first place.

When held against the backdrop of the technical developments over the last 20 to 30 years – first with image editing software, then with digital photography and image rendering, and now with AI being able to create realistic images in a split second that lack any relation to reality – Voïta’s engagement with photography feels visionary. He has taken a literally handmade, almost DIY approach to the medium’s determining technical and cultural attributes at a specific, transitional point in history, one that helps us to understand that photography, with its presumably privileged and objective access to reality, may have been a historical anomaly – a strange knot, in which technological developments and a cultural and social urge for unified vision were joined together for no more than a limited period.

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Camera I, IV, VIII’, 2003, silver gelatin print on paper, 48.5 x 47 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Camera I, IV, VIII’, 2003, silver gelatin print on paper, 48.5 x 47 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Historical Perspectives

Fittingly, Voïta’s interest in the technologies we use to make sense of the world extends far back into

history. Before photography, there was the ‘camera obscura’, the ‘laterna magica’, or even Albrecht

Dürer’s ‘perspectograph’, all of which Voïta shows in his ‘Melencolia’ catalogue – devices that allowed

for the almost automatic creation or projection of images of the world we see and perceive. In his 2009

series ‘Paysage ahah’, which is part of the Julius Baer Art Collection, Voïta returned to another

historical invention regarding the development of perspective and its role in image-making and

perception.

These works – once again showing images from Voïta’s studio, only this time overlaid with other photographs printed directly on the covering glass – refer to a device from landscape architecture that essentially enabled the change from the strictly geometrical gardens of France to the more open English landscape gardening, which preferred fluid lines and the occasional distant view. Whereas once conventional walls confined a visibly artificial garden, these walls and borders became rendered invisible by simply lowering them into a trench. The garden now seemed open and endless, a part of nature. Visitors often reacted with a surprised ‘aha!’ – much like a spectator may do when experiencing Voïta’s work.

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Paysage ahah #10, #11’, 2009, coloured inkjet print on paper on glass, 73 x 57 x 4 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Paysage ahah #10, #11’, 2009, coloured inkjet print on paper on glass, 73 x 57 x 4 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

The subtle humour, however, that cheeky ‘aha!’ becomes most apparent in the last work by Voïta that can be found in the Julius Baer Art Collection, namely ‘Jalousie III’ from 2017, a wall-mounted metal sculpture made from various geometric parts. The work’s separate elements are connected with hinges and can be folded out. When closed, the work – as with the others in the same series – resembles an abstract and geometric painting, but when opened it seems to come to life, stretching out its limbs, or its trunk, for that matter, into the room. Here it is, then, occupying space, claiming its presence, only now on this side, on our side of the image. It is sharing the room with us, wanting to be touched, palpated and made sense of – much like the elephant on the cover of Voïta’s book.

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Jalousie III’, 2017, lacquered steel, closed: 80 x 62 x 7 cm, unfolded: 197 x 62 x 112 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Bernard Voïta (b. 1960), ‘Jalousie III’, 2017, lacquered steel, closed: 80 x 62 x 7 cm, unfolded: 197 x 62 x 112 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Author: Dominikus Müller

Don’t miss the exhibition ‘Bernard Voïta – Der Streit der Blinden’ at Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, until 6 October 2024.