Chloé Delarue: Art and the humanity of tech

Chloé Delarue in her studio in Geneva, Switzerland.

Chloé Delarue in her studio in Geneva, Switzerland.

By bringing together familiar materials and combining them in unfamiliar ways, Chloé Delarue’s installations produce a disquieting effect. The fierce light emitted from her sculptures evoke a sense of endless day. On some levels we know what we see, but how do we make sense of it all put together in this way? Our senses – sight, sound, even the smell of latex – are awakened and our minds begin to whir.

This is TAFAA – an ongoing series of sculptural environments begun in 2015 by the Geneva-based artist Delarue. The assemblages incorporate readily available industrial objects with fabricated components, using metal, Perspex, and glass, with fluorescent tubes and neons. Added to this is an organic element – most commonly latex, stretched across screens, hanging in swathes.

Chloé Delarue lives and works in Geneva, Switzerland. She produces installations (sculpture and video) under TAFAA.

Chloé Delarue lives and works in Geneva, Switzerland. She produces installations (sculpture and video) under TAFAA.

The TAFAA acronym stands for ‘Toward A Fully Automated Appearance’ and is derived from an article written by American economist Fischer Black in 1971, titled ‘Toward a Fully Automated Stock Exchange’. In this body of work, Delarue examines the relationship between technology and living beings. She is interested in the automisation of labour and the way in which technology transforms our perceptions and our emotions.

Research: In the Studio & Beyond

Born in France in 1986, Delarue studied first at the École Nationale Supérieure d'Art – Villa Arson in Nice, moving to Switzerland to complete a Masters at HEAD-Genève in 2014. The recipient of numerous awards including the prestigious Pax Art Award in 2021, Delarue will soon embark on a residency at the Cité internationale des Arts in Paris as well as at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) astronomy facilities in Chile, end of 2023.

Her working process is a combination of material experimentation in the studio and what she terms ‘drifting into simulated environments to observe the transformation of reality as it is filtered by the appearance of immediacy’. She shifts back and forth between the two, creating a flow of information, and is interested in political and social subject matter. Her broad range of interests spans science, technology, and popular culture through the lens of this digital world.

Delarue has been commissioned to make a work for the new CERN Science Gateway project, an impressive exhibition and education centre opening in her hometown in 2023. Her relationship with CERN began when she was invited to participate in their Simetría residency in 2021. As the site of world-leading scientific research, it could be a daunting setting for someone without a scientific background, but Delarue explains, ‘As you cannot understand everything, the power of the imagination is always reassuring in the face of the tender anxiety of the universe’s complexity.’ For her it was a fascinating opportunity to observe the scientists at work, to appreciate the passion of those carrying out the research, and enjoy the storytelling and poetic potential of the experience. This pioneering and innovative context chimes with Delarue’s ability to harness the energy of change in her practice, thereby allowing that she herself becomes a change maker.

Her ongoing body of work attempts to capture the instabilities of our time.

Her ongoing body of work attempts to capture the instabilities of our time.

‘Only Relics Feed the Desert (Halo)’ (2021)

Of Julius Baer acquiring her work, Delarue says, ‘It was with great pleasure that I learnt one of my sculptures had entered the collection – and particularly a piece from this new body of work.’

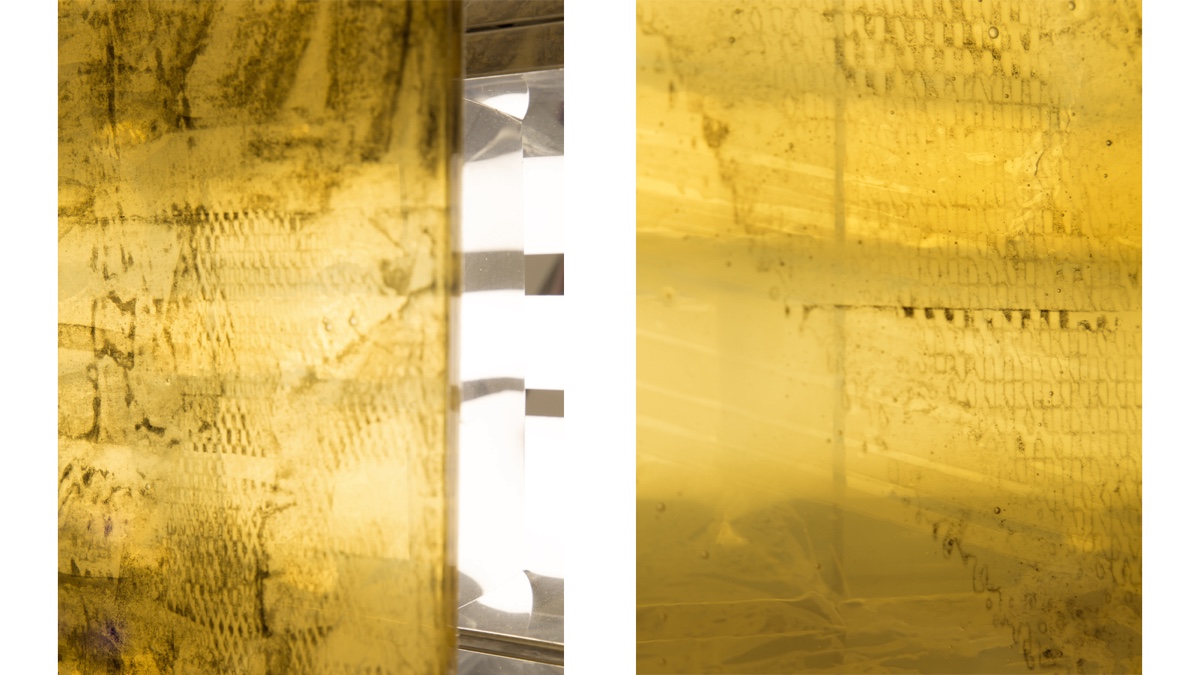

The work selected is, ‘TAFAA – ONLY RELICS FEED THE DESERT (HALO)’ (2021), in which a metal frame leans against the wall, with two parallel sheets of latex hanging down, lit from behind by the harsh glow of fluorescent tubes within the structure. An image is printed onto the latex, or rather embedded within its layers. It is ambiguous, somewhat unclear, but appears to be a human figure – a kind of ghostly apparition. Almost like a version of a stained-glass window, the image is in fact a religious icon borrowed from a video game.

Two different views of 'TAFAA - ONLY RELICS FEED THE DESERT (HALO)', 2021, aluminium, fluorescent tubes, glass, latex, transfer printing, cables, ballast, 228 x 60 x 40 cm, by Chloé Delarue (b. 1986), courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Two different views of 'TAFAA - ONLY RELICS FEED THE DESERT (HALO)', 2021, aluminium, fluorescent tubes, glass, latex, transfer printing, cables, ballast, 228 x 60 x 40 cm, by Chloé Delarue (b. 1986), courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Here, as in other works by Delarue, technology combines with the organic in an uneasy marriage. The latex suggests a human or animal skin that has been shed. Extending this anthropomorphic reading, the trailing cables become guts. These somewhat jarring juxtapositions of the natural and human-made, mirror our dependency on technology and the uncompromising and uneasy nature of this relationship.

Detail of 'TAFAA - ONLY RELICS FEED THE DESERT (HALO)', 2021, by Chloé Delarue (b. 1986), courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Detail of 'TAFAA - ONLY RELICS FEED THE DESERT (HALO)', 2021, by Chloé Delarue (b. 1986), courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Subtitles of works often provide an explanation or a key, but for Delarue they introduce a softer, more poetic, or even allegorical element. In this case, the subtitle re-establishes the human, evoking ideas of mortality and religion. It simultaneously unlocks and obscures the intentions behind the piece.

In engaging with the impact of technology on our lives, it is notable that these works present neither as optimistic nor pessimistic. Instead, Delarue observes: ‘For me it is very important not to be positive or negative. I am not looking to pass judgment or be prescriptive. As an artist, my interests are first and foremost to produce a particular aesthetic in relation to my reflections and think about how my work affects the audience by stimulating the different human senses.’

Author: Sara Harrison