Sound images: the art of Christian Marclay

Portrait of Christian Marclay, photo: The Daily Eye

Portrait of Christian Marclay, photo: The Daily Eye

Christian Marclay (b. 1955) composites ideas through the materials he arranges, recycles, and reimagines. Many bios cite the Swiss-U.S. artist and composer as a pioneer of DJing, as Marclay began experimenting in the late 1970s with records and turntables to mix sounds. Since then, Marclay has continued to puzzle together sounds, films, printed matter, and canvases – configurations that encourage sensory correspondences. These correspondences can be seen in the dozen Marclay works that have a home in the Julius Baer Art Collection as well as in the artist's solo exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris on view through 27 February 2023.

Sculpting sounds via found records was an artistic departure point for Marclay. He continued using records in his work, pushing the creative possibilities of pressed discs as a medium for making art. Through his practice, Marclay developed his Recycled Records series (1980−1986)—playable fragmented and reconstructed record collages—and his Body Mix series (1991−1992), which consist of stitched-together album covers that convey a contemporary take on the Surrealist "exquisite corpses" game used to generate collaborative images.

Marclay’s art calls up a range of sensory reactions: noises, words, graphics and objects take on new narratives. This calling is quite literally elicited with ‘Telephones’ (1995), one of the earlier Marclay works in the Julius Baer Art Collection (the Pompidou exhibition features a sister edition). ‘Telephones’ is a single-channel video featuring colour and black-and-white scenes from 130 Hollywood films. For seven-and-thirtyfive minutes, it follows the arc of a telephone call with spliced-together footage of cinematic dialling, ringing, answering, conversation (or lack thereof) and the inevitable dismount—goodbyes, hang-ups and endings.

Christian Marclay (b. 1955), stills from: ‘Telephones’ (1995), single-channel video, colour and black-and-white,

sound, 7 minutes 35 seconds, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Christian Marclay (b. 1955), stills from: ‘Telephones’ (1995), single-channel video, colour and black-and-white,

sound, 7 minutes 35 seconds, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

For Marclay, composing with both preexisting sounds and images as mediums was a more complex undertaking than his earlier mixing of sounds from found records. In the Centre Pompidou exhibition catalogue, Marclay describes that in ‘Telephones’, "sound and image are treated in the same way, one is not more important than the other and they are complementary." When piecing the work together, he "looked for actions and sounds in cinema from which to create a musical composition, like a DJ, but with sonic images."

“The relationship between sound and image has always intrigued me,” Marclay explained in a conversation with Jean-Pierre Criqui, the curator of the Centre Pompidou exhibition. “’Telephones’ is the first video for which I sampled from the history of cinema,” he expressed. “I’ve always had this impulse to make collages, whether with found objects or printed material, or with sound. Why not react to what already exists around you, rather than reinventing the wheel?”

There is sincere artistic heritage in Marclay’s work; when surveying his record-related art and his progression into film, one feels the presence of French artist Marcel Duchamp. Forty years earlier, Duchamp produced his kinetic Rotoreliefs—soundless discs printed with images and puns that create optical illusions when spun—that are the subject of the artist’s short film ‘Anémic Cinéma’ (1926). Marclay revered Duchamp; in the 1970s, Marclay joined the “Bachelors, Even,” an art band named after ‘The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even’, Duchamp’s seminal artwork (also known as ‘The Large Glass’).

As a student at the Ecole Supérieure d'Art Visuel in Geneva (1975–1977), Marclay engaged with minimalism; in an abandoned Caran d’Ache pencil factory, he employed found objects to create installations. He was drawn to the Fluxus art collective, particularly to the work of Joseph Beuys, one of the collective’s founders, along with the American avant-garde composer John Cage, a close Duchamp comrade whose experimental music was integral to the grounding of Fluxus. Marclay activated the influence of these artistic predecessors; in his work, viewers see art-historical dominoes that tip from Duchamp’s wordplay to Fluxus’s multiples to Pop Art’s bright canvases

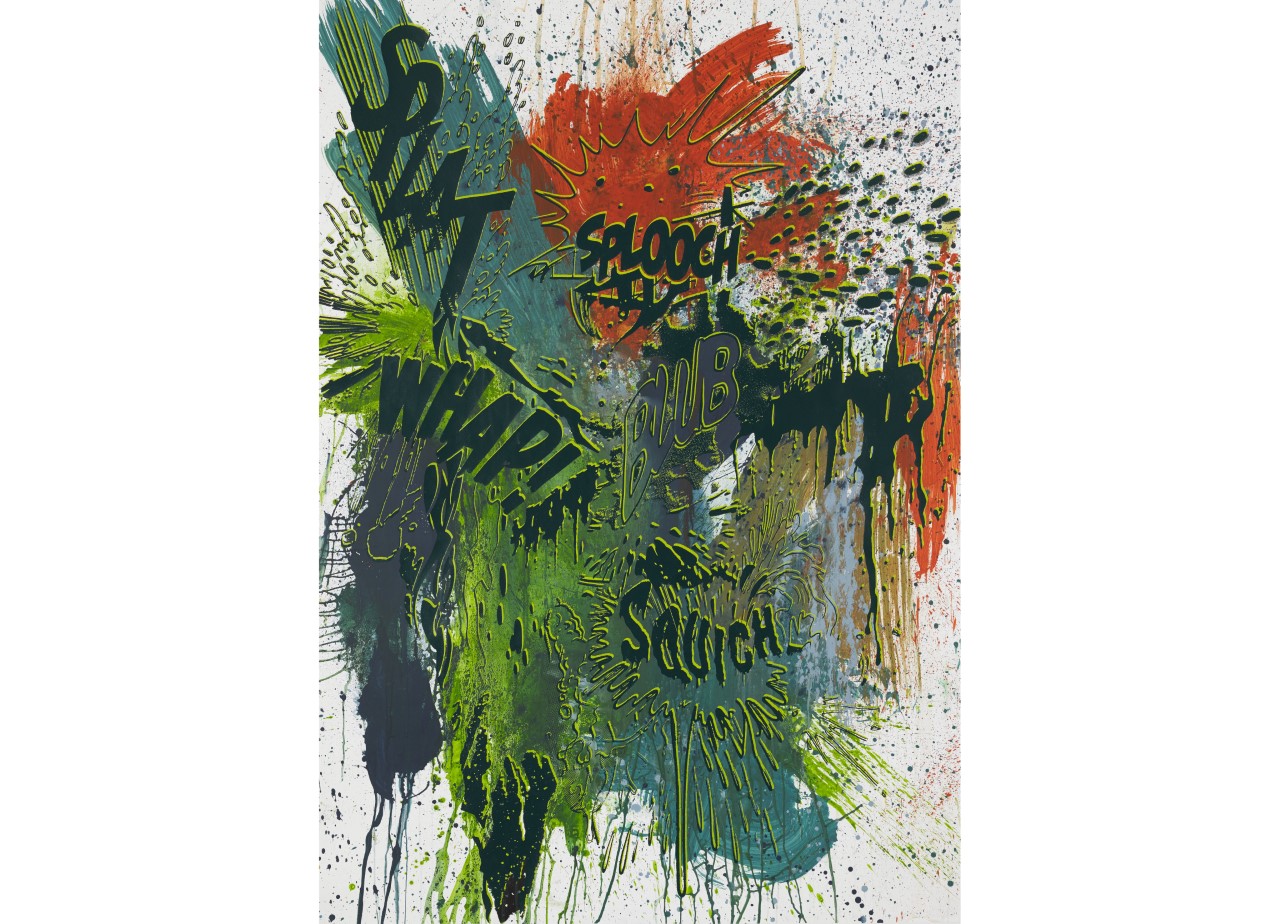

Christian Marclay (b. 1955), ‘Actions: Splat Splooch Whap Blub Squich’ (2014),

screen-printing ink and hand-painted acrylic on paper, 213.5 x 148.2 cm,

courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Christian Marclay (b. 1955), ‘Actions: Splat Splooch Whap Blub Squich’ (2014),

screen-printing ink and hand-painted acrylic on paper, 213.5 x 148.2 cm,

courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

This is the case with Marclay’s large-scale Action series to which the Julius Baer Art Collection’s ‘Splat Splooch Whap Blub Squich’ (2014) belongs. In line with this series, ‘Splat Splooch Whap Blub Squich’—a screen-printed and hand-painted work on paper—employs onomatopoeia in comic-strip scrawl to illustrate liquid sounds that gush and ooze with colour and form. These vivid, graphic representations continue Marclay’s career-long exploration of sounds and images. His technique is so successful in these works that Merriam-Webster lists a quote from Marclay in its definition of onomatopoeia: "In comic books, when you see someone with a gun, you know it's only going off when you read the onomatopoeias."

Being cited in a renowned dictionary is a special kind of career highlight—one of many Marclay can count to his name. Another, perhaps more famous recognition of his cultural impact is the Golden Lion award that he received at the 49th Venice Biennale for his epic work ‘The Clock’ (2011), a 24-hour film collage in the vein of ‘Telephones’. In addition to his current exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Marclay’s work has been exhibited widely at some of the world’s most revered art museums, with recent solo shows at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Geneva (2020); Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California (2019); Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain (2019); and Sapporo Art Museum, Japan (2017).

An exhibition at an institution like Centre Pompidou is a momentous occasion in an artist’s career, although Marclay sees it as another launching point. For him, the exhibition is “a stopover; it constitutes a survey, a panorama. It doesn’t show everything, obviously choices have to be made. It’s a look back at the landscape I’ve already travelled,” he expressed to Clique, the exhibition’s curator. “But I am impatient to get back on the road because I still have many things to discover."

Jennifer Magee