Markus Raetz: The Wandering and Wondering Eye

The late Swiss artist Markus Raetz spent a lifetime pursuing questions of perception and perspective and created an utterly unique and stunningly beautiful oeuvre. Currently, the first posthumous retrospective of Raetz’s delicate works is on view at Kunstmuseum Bern.

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Untitled’, 1981, watercolour on paper, 24 x 32 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Untitled’, 1981, watercolour on paper, 24 x 32 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

It doesn’t take much to recognise Elvis, the king of rock ‘n’ roll. His haircut is enough. One is immediately reminded of the iconic nature of this central figure of post-war culture when looking at the eponymously titled ‘Elvis’, an early work by Markus Raetz which the artist created in 1967. Here, too, the ‘king’ can be instantly identified by the shape of his head and emblematic haircut. Yet ‘Elvis’, with its bright colours and the pop art vocabulary so typical for the swinging 1960s, may not be all that characteristic when we think about Raetz’s own highly recognisable clean and reduced style that would be developed and refined in the decades to come. However, this early work, which is part of the Julius Baer Art Collection, already shows some of the critical features of Raetz’s approach in a nutshell, even if they are somewhat hidden.

When scanning the work in its entirety, one can’t help but realise that the strange amorphous form repeated in the background is, in fact, rather more concrete than abstract: It is the shape of the area around Elvis’ eye that seems to have wandered sideways, out of the king’s face. But to recognise this, the viewer’s eye must itself wander sideways across the picture. It is a great, if somewhat concealed embodiment of what Raetz’s work was concerned with for decades – perception and ways of seeing, and how this relates to movement, angles and perspectives.

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Elvis’, 1967, gouache on paper, 50 x 70 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Elvis’, 1967, gouache on paper, 50 x 70 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Drawing the World

But first, Raetz himself had to wander off to see the world. Born in Bern to parents who were teachers,

he briefly worked as a teacher himself before eventually deciding to go all in as a contemporary artist

– and with famous curator Harald Szeemann at the helm of Kunsthalle Bern, Raetz’s hometown was the

perfect place in the 1960s to get in touch with the newest trends in conceptual art. In 1969, Raetz and

his wife Monika moved to Amsterdam for a few years. A three-year stint in the small Ticino village of

Carona followed before they eventually returned to Bern in 1976. Several sketchbooks and countless

drawings document the frequent travels of the 1970s, including extended journeys to Spain and Morocco

and long stays near the French town of Ramatuelle on the shores of the Mediterranean.

Drawing, during these years, became Raetz’s predominant medium of expression. It was a means of instantly recording what he had seen with just a few lines – filtered through his eyes and his fingers. It is an ever-meandering flow of images, day after day, year after year, a lifetime – a testament to his point of view, his specific vision, and his position in the world. It comes as no surprise that eyes feature prominently in many of these drawings: they multiply or glow strangely; they get dragged out of the face by two hands or are replaced by the growing branches of a tree; then there are the eyes dripping down like water droplets in works like ‘Tropf’, 1971; and sometimes they even take on the form of nothing more than two simple holes through which we see the horizon – a perspective, indeed; Raetz’s perspective.

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Tropf’, 1971, ink, pencil and watercolour on paper, 21.1 x 29.8 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Tropf’, 1971, ink, pencil and watercolour on paper, 21.1 x 29.8 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Reduction and Recognition

Time and again, the artist, who participated four times in the world-famous documenta show in Kassel,

Germany, and represented Switzerland at the Venice Biennale in 1988, addressed movement and its relation

to perception, metaphorically and literally ‘circling’ his subject. Take a work like the eight-part

‘Bewogen beweging’, 1982, from the Julius Baer Art Collection. Raetz sketches a male head here with just

a few lines. On each new piece of paper he slightly changes perspective, much like a camera moving and

circling the head: click, click, click. The world is not a fixed entity. It is open to endless

interpretations and countless perspectives, seen from many angles. And with every instant, from each new

position, it changes face.

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Bewogen beweging’, 1983, Indian ink on silk paper, mounted on cardboard,

8 parts, each 43.8 x 34.6 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘Bewogen beweging’, 1983, Indian ink on silk paper, mounted on cardboard,

8 parts, each 43.8 x 34.6 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

In many works, Raetz played up reduction and ephemerality even further, eventually reaching a radically economical gestural vocabulary located right at the tipping point where a few abstract lines suddenly start to turn into the most simple but recognisable, almost archetypical figurative motifs. He hastily sketched bodies and torsi into the sand of the Mediterranean shores of Ramatuelle, photographing them before the waves washed them away, or, for a while, used Eucalyptus branches or even leaves instead of a pen to arrange simple forms on the walls. Often, these were faces – a laughing one here, a rather grim one there. From today’s perspective, these works, as reduced markers of feeling, appear to be analogue predecessors of the ubiquitous emojis and pictograms populating our digital screens.

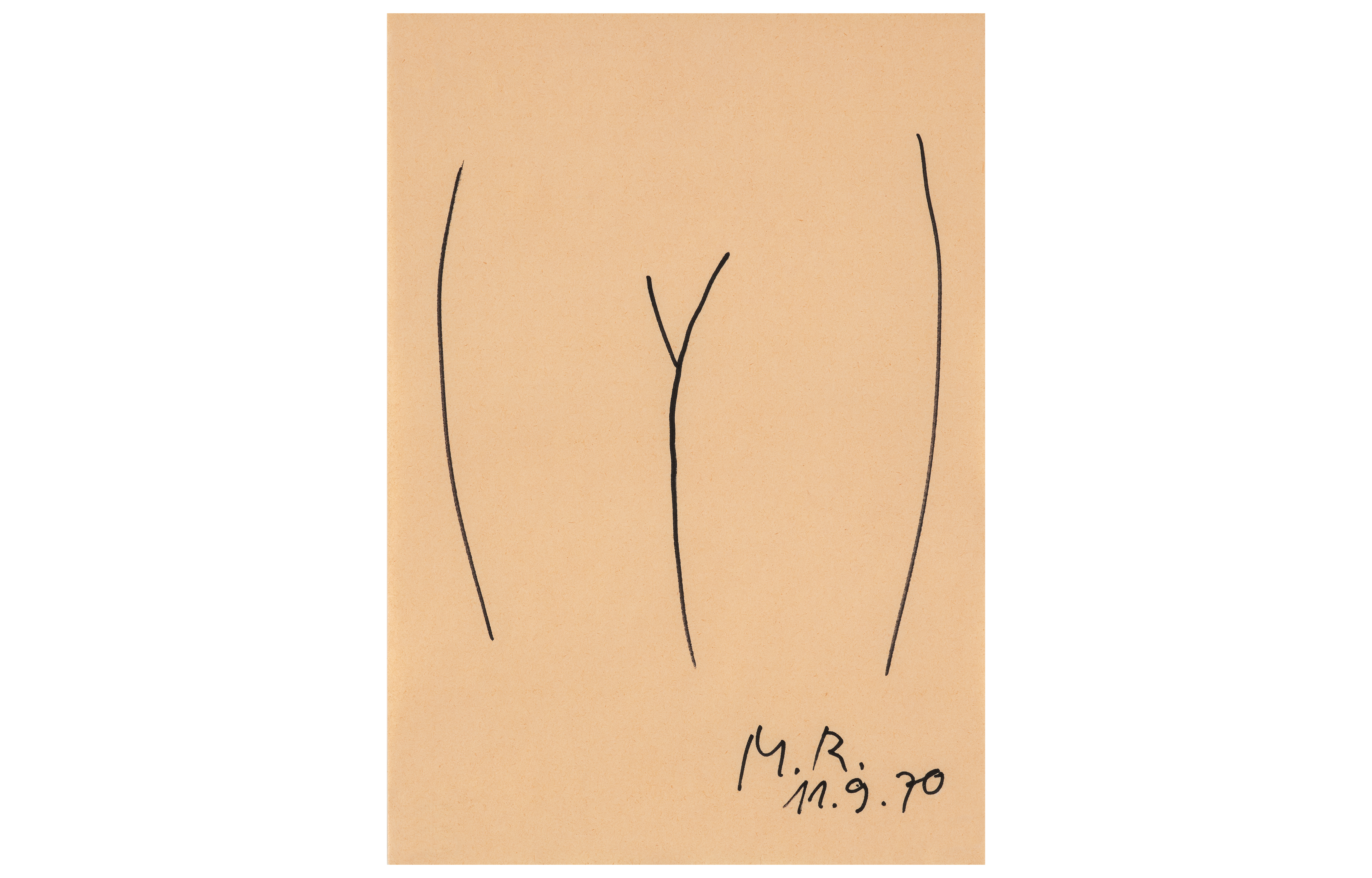

For ‘EVA’, 1970 – currently on view in the first posthumous retrospective of Raetz’s work at Kunstmuseum Bern – the artist used a few bare branches and some lumps of plasticine to assemble a sculpture of a woman’s hips and crotch that feels much like a three-dimensional drawing. And indeed, in the Julius Baer Art Collection one can find a work on paper with this motif, too.

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘EVA’, 1970, marker on paper, 29.6 x 20.9 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Markus Raetz (1941–2020), ‘EVA’, 1970, marker on paper, 29.6 x 20.9 cm, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich, courtesy Julius Baer Art Collection

Moving Sculptures and Changing Perspectives

As can be seen in the Kunstmuseum Bern retrospective, at some point Raetz arrived at a sculptural

practice that managed to bring movement and a change of perspective back into the works themselves – a

perfect mixture, as it were, of drawing’s simple lines and the depth of three-dimensional space. There

are anamorphic pieces forming words that read ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ from different perspectives (or ‘Oui’ and

‘Non’). And there are Raetz’s mobiles, mostly thin wires bent into abstract forms or delicate reduced

drawings, often faces, seemingly floating weightless in space, spinning around their axis – this is not

only a three-dimensional drawing but an animated one, too.

From today’s perspective, where political and biographical aspects frame much of contemporary art’s reception and production – a different sort of ‘positioning’ – Raetz’s oeuvre may, at first, appear all too concerned with radically formal and abstract issues. Yet isn’t the central question that this artist used to spend a lifetime exploring far more political than it initially seems? He insisted that perception relies on and is utterly dependent on position and perspective – and that things can drastically change when we move a few steps to the side, taking a different perspective and seeing the world from another angle. Isn’t this a profoundly political experience, after all? Raetz, in all modesty and with a decidedly tacit and quiet humour, time and again reminds us of the fact that things, quite literally, are in the eye of the beholder. And it is us who have to make a move.

Author: Dominikus Müller