Meret Oppenheim: Subconscious Explorations

Meret Oppenheim 1983, Estate of Meret Oppenheim, photo: Nanda Lanfranco

Meret Oppenheim 1983, Estate of Meret Oppenheim, photo: Nanda Lanfranco

In 1932 at the age of 18, Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985) uprooted from Basel, Switzerland and left for Paris, France, the locus of the burgeoning Surrealist movement. When Oppenheim touched down in the Surrealist’s Parisian nest, her primary mediums were poetry, drawing, and watercolour. She arrived as a natural-born Surrealist equipped with a profound curiosity and understanding of dreams and the subconscious—an interest she grew up sharing with her father, a doctor, who was acquainted with psychoanalyst Carl Jung and closely followed his work. Oppenheim’s early inquisitiveness developed into a lifelong exploration of the subconscious, the primary source material from where she plumbed her creations that lace together more than a half-century of her artistic output.

Oppenheim, who was taking art classes at Paris’s Académie de la Grande Chaumière, quickly infiltrated the circle of male-dominated Surrealists through her alliances with fellow Swiss artists Alberto Giacometti and Hans Arp. While sitting in a café with Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso in 1936, Oppenheim conceived her fur-lined cup—a work that enchanted Surrealist co-founder André Breton, who selected it for display in the first exhibition of Surrealist sculpture and renamed it ‘Le Déjeuner en fourrure’. Oppenheim’s cup became known as one of the movement’s iconic works, with its expression of a dark, layered humour and sexuality through an ironic and unexpected distortion of an everyday object. It is representative of the interwar period’s intellectual and artistic tectonic plate shift—an art history that is under revision, as Oppenheim’s and her female artistic peers’ achievements are only beginning to be integrated with those of their male counterparts, who include Man Ray and Salvador Dalí.

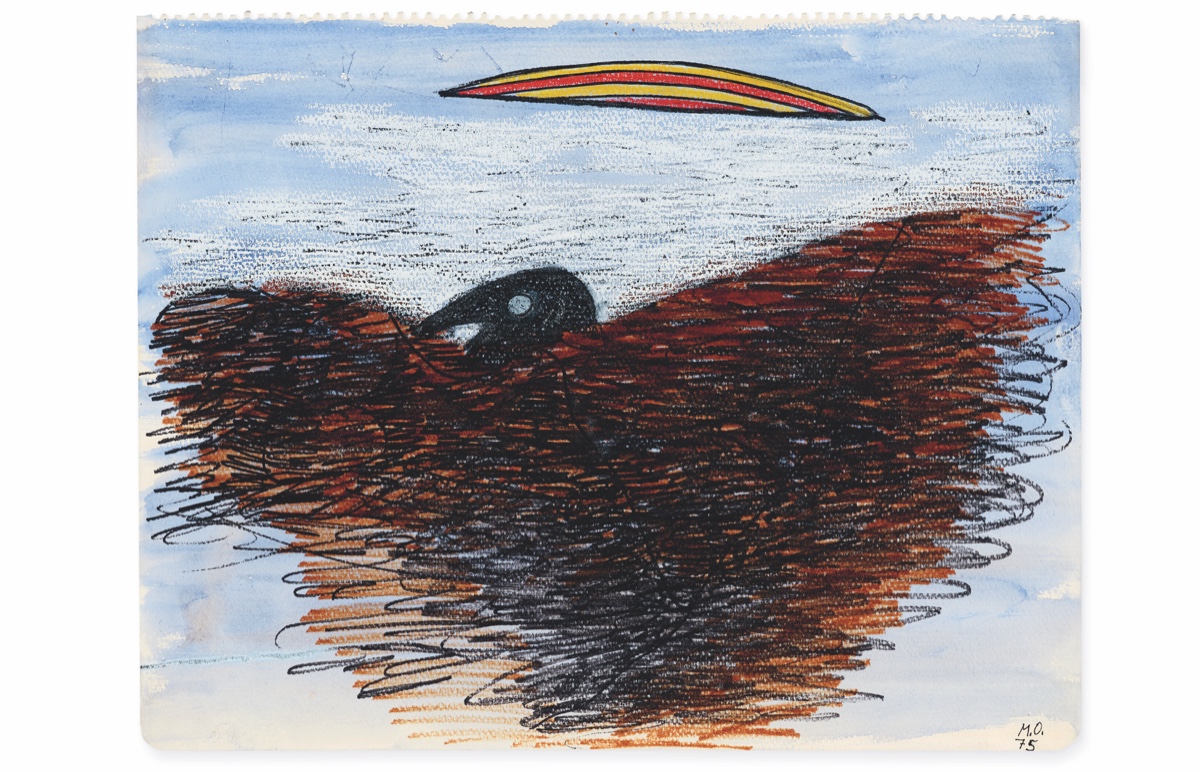

Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), ‘Geier und gelb-roter Gegenstand’, 1975, watercolour, pastel and charcoal on paper, 26 x 34 cm, courtesy the Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich, photo: David Aebi

Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), ‘Geier und gelb-roter Gegenstand’, 1975, watercolour, pastel and charcoal on paper, 26 x 34 cm, courtesy the Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich, photo: David Aebi

Moulding the Immaterial: Oppenheim’s Drawings in the Julius Baer Art Collection

Now known as one of the defining artists of Surrealism and twentieth-century art and a foundational figure for

contemporary artists, Oppenheim and her enduring talent are posthumously acknowledged with multiple exhibitions

and publications dedicated to her work. This includes a show at the Kunstmuseum Solothurn titled ‘Meret

Oppenheim (1913–1985): Arbeiten auf Papier’ that features two of the artist’s drawings from the Julius Baer Art

Collection: ‘Brasilia und die grosse Erdschlange’ (‘Brazil and the Great Earth Snake’) from 1968 and ‘Geier und

gelb-roter Gegenstand’ (‘Vulture and Yellow-Red Object’) from 1975. Both works communicate Oppenheim’s continued

expression of the subconscious, which remained the font of her creativity long after she left the Surrealists

and continued her artistic evolution.

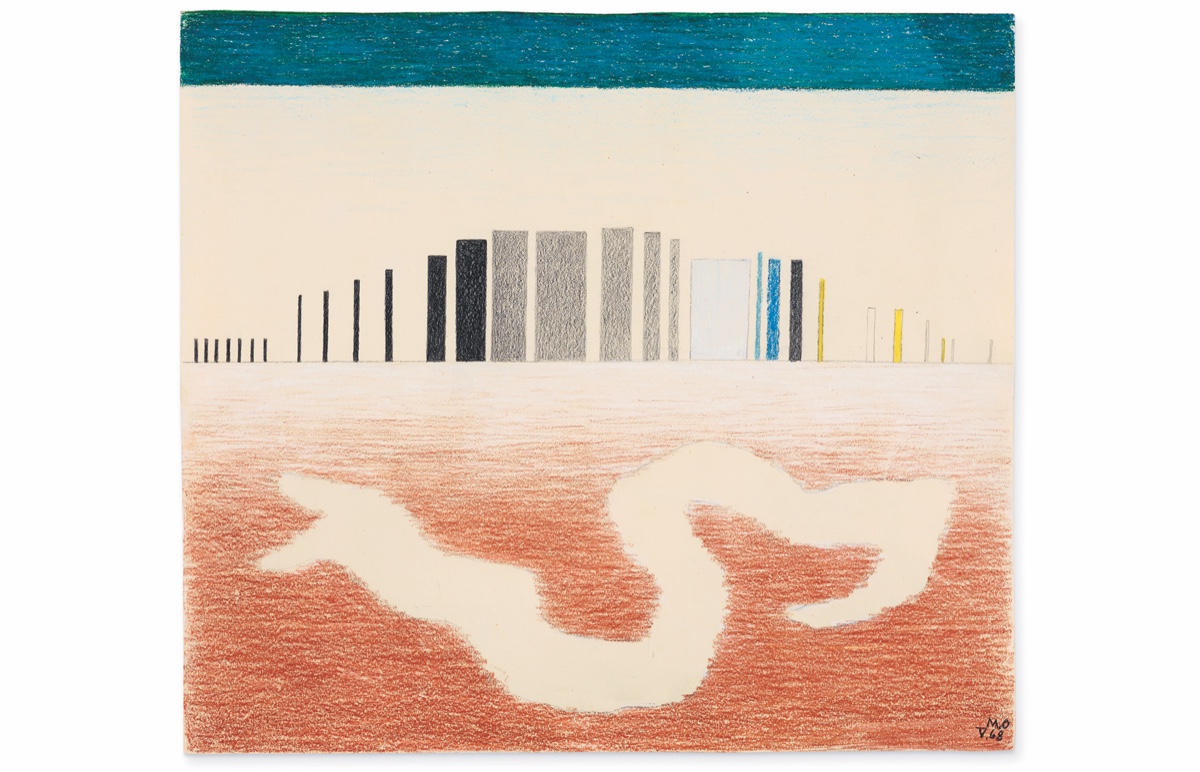

Lisa Wenger, Meret Oppenheim’s niece, describes that the 1968 drawing was made after her aunt’s trip to Brazil in 1967 for the Biennale and that the ‘Erdschlange’, the Earth Snake, was an important theme for her aunt. “The subterranean snake connects to the subconscious,” Wenger explains, and “dreams are an expression of that realm.” In addition, this work evokes how Oppenheim looked to nature and the world around her for inspiration: snakes, butterflies, birds. These inspirations and expressions extend to the drawing ‘Geier und gelb-roter Gegenstand’. Wenger describes how birds often appear in Oppenheim’s drawings, and she finds their dreamlike qualities are renderings of her aunt’s subconscious.

Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), ‘Brasilia und die grosse Erdschlange’, 1968, pastel crayon and pencil on paper, 37 x 42 cm, courtesy the Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich, photo: David Aebi

Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), ‘Brasilia und die grosse Erdschlange’, 1968, pastel crayon and pencil on paper, 37 x 42 cm, courtesy the Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich, photo: David Aebi

While discussing the meaning of Oppenheim’s birds, Wenger notes that another theme often present in her aunt’s work are clouds that appear to be held up by something else, like a bridge or sticks. Wenger describes this device as “an engagement with the immaterial that is not possible with the actual material,” underscoring how Oppenheim’s art moulds the immaterial: clouds, dreams, and the subconscious.

Unbound and Unclassified

Artistic freedom was a constant in Meret Oppenheim’s oeuvre. From still-life gouaches to an evening jacket with

plate buttons and embroidered cutlery, from an X-Ray of her skull to an oil painting culled from Greek

mythology, and from published poems to a towering brutalist spiral-shaped water fountain, Meret Oppenheim eluded

conventions and classification throughout her career—the diversity of her styles across her oeuvre showcase her

polymath artistic talent and boundless imagination. She was not interested in becoming a commercial artist, and while in Paris, she supported herself financially by making fashion and jewelry designs that she sold to

Surrealist fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli. When she returned to Basel, Switzerland in 1937, she trained and

practised as an art restorer, a craft that allowed her to study materials and fix her own works—making her an

all-in-one artistic service, from conception to conservation. Her creative practice continued, and in the late

60s and 70s, when Oppenheim made the two drawings that are now part of the Julius Baer Art Collection, she

remained unsubscribed to any one medium. Although she generated many drawings in those years, she was also

painting, making monumental sculptures, and revisiting her fur cup, ‘Object’ (‘Le Déjeuner en fourrure’), from

many decades before, while also generating graphic works, multiples, and writing.

Meret Oppenheim’s studio at Ziegelstrasse 30 in Bern, Estate of Meret Oppenheim

Meret Oppenheim’s studio at Ziegelstrasse 30 in Bern, Estate of Meret Oppenheim

Oppenheim refuted categorisation on all levels, and she strove to evade critical compartmentalisation. To this end, she also rejected a feminist approach to her work and chaffed when classified as a “woman artist”—a generalisation she found constraining; Oppenheim rightfully believed that her works should exist in a more diverse realm with her male contemporaries. This steadfast commitment to remaining undefined extended to her love life; she asked that her letters with Marcel Duchamp not be disclosed until after her death, an active attempt to avoid the details of her intimate relationships eclipsing her art.

Such correspondence is included in the award-winning book ‘Worte nicht in giftige Buchstaben einwickeln’ (‘Don’t Wrap Words in Poisonous Letters’), an impressive collection of sixty-five years of Oppenheim’s letters assembled by Lisa Wenger and Martina Corgnati. Wenger poured over her aunt’s archive for more than a decade, sifting through Oppenheim’s correspondence with family and artist friends—André Breton, Leonor Fini, and Max Ernst, among others. Together, these documents offer new perspectives on Oppenheim’s thinking and approach to making art.

Since taking over the management of Oppenheim’s estate with her cousin Martin A. Bühler, Wenger, too, has come to know her aunt: “I’ve gained great insight to Meret from this work. It’s a joy, an honour.” With a radiant laugh, Wenger adds: “Honestly, it is also sometimes a bit of a pain.” After all, Wenger did transcribe well over one thousand documents—many of which were handwritten in challenging and somewhat illegible script—from Oppenheim’s archive.

And it is through Oppenheim’s incredible body of work—written and visual—that she continues to shape, write, and inspire the ongoing story of art history.

Author: Jennifer Magee