Miriam Cahn’s Intimate Confrontations

Portrait of Miriam Cahn, photo: François Doury

Portrait of Miriam Cahn, photo: François Doury

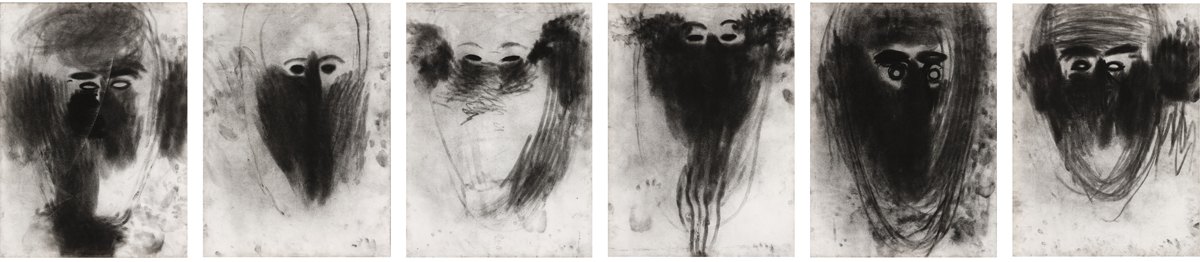

Cavernous eyes – their contours definitive and sure – glare out from faces rubbed with charcoal veils in Miriam Cahn’s 1985 drawings titled ‘L.I.S. . . . Hinsehen’ (Look At). L.I.S., Cahn’s shorthand for ‘Lesen im Staub’ or ‘reading in dust’, is an apt name for this series and its eyes that drill through the charcoal’s porous carbon to confront viewers with a dark, knowing strength.

The Julius Baer Art Collection houses six of these powerful L.I.S. drawings, along with more than twenty other works by Cahn that render a larger picture of the artist’s forceful oeuvre. They track her transition from drawing to painting and from black and white to colour, culminating in the collection’s recent acquisition of ‘Blumenfamilie in meinem Garten’ (Flower Family in My Garden), a 2017 oil painting.

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘L.I.S. …Hinsehen’, 1985, charcoal on paper, 6 parts, each 76 x 56 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘L.I.S. …Hinsehen’, 1985, charcoal on paper, 6 parts, each 76 x 56 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

“The complexity of it all”

“My work has a lot to do with showing the complexity of it all, between sex, power, aggression, and

everything like this”, Cahn said. Through the decades she has engaged with the women’s movement, and her

work often articulates the inner life of women, the brutality of their societal existence and

hierarchical struggles. In addition to women, Cahn’s primary artistic subjects include sentient beings

and the natural world, expressed through her portraiture’s focused individualism. Themes of desire,

vulnerability and the brutality of war and torture emerge through her works on paper, performance,

painting, text and film.

Born in 1949 in Basel, Switzerland, Cahn now resides in the canton of Graubünden’s Bergell region, known as ‘the valley of the artists’, home through the centuries to esteemed creatives that include Varlin (1900–1977), Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) and the Giacomettis. In Basel, Cahn grew up in a family where art and music were embraced, and from 1968 to 1973, she trained as a graphic designer at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel (now called the Schule für Gestaltung Basel).

Following her studies, Cahn taught drawing and worked as a scientific draftswoman until 1976, when she cites making her first artworks. She began with small drawings and then undertook temporal performance drawings on Basel’s streets and underpasses. She was charged with criminal damage to public property for the latter actions.

By the time she completed her L.I.S. drawings in the mid-1980s, Cahn’s work had been selected for documenta 7 in Kassel (1982; Cahn withdrew her work before the opening following a curatorial blunder), the 41st Venice Biennale (1984) and a group exhibition at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (1984). Numerous international exhibitions and awards have followed her esteemed career, including a major retrospective of her work titled ‘My Serial Thought’ at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, France, on view until 14 May 2023.

Cahn’s portraiture: Women who look back

The Julius Baer Art Collection has faithfully supported and collected Cahn’s art throughout her career,

beginning in 1988 with the acquisition of her L.I.S. series, along with six charcoal drawings made in

1985, all titled ‘Sie will den Kopf nicht senken’ (She Will Not Lower Her Head, 1985).

In these latter works, as with Cahn’s L.I.S. drawings, there is a sense of power and poise in how the subjects’ eyes meet the viewer. “My females look back”, Cahn said of this effect. The artist often hangs her works on her own, positioning the portraits at the viewer’s eye level to integrate the audience. “Is it still erotic if a woman looks back? It’s very different, it’s more active”, she explained. “It’s very important that women look back at the viewer, rather than their heads being obscured.”

Moving from black and white to colour

In contrast to Cahn’s stark, black-and-white heads of the 1980s, the artist began using colour in the

1990s, as seen in ‘Untitled’, 1993, and ‘Männer’ (Men, 1993) – two further series of Cahn’s ‘head’ works

on paper in the collection. Both are composed of pigment and glue rather than charcoal.

Cahn has an uncanny ability to communicate intense emotional vibrations with charcoal’s limited range, and her application of colour appears like a weather map of raw feeling – heat and anger emanating from red and orange hues, such as those seen in the ‘Männer’ (Men) series.

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘Männer’, 1993, pigments and glue on paper, 8 parts, various dimensions, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘Männer’, 1993, pigments and glue on paper, 8 parts, various dimensions, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

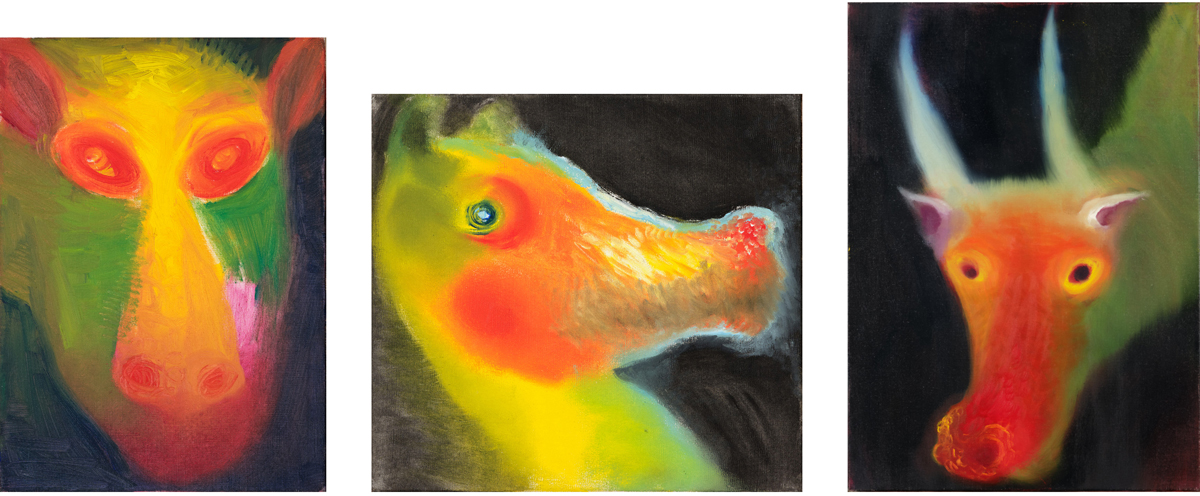

As with Cahn’s head portraits, in her small oil-on-canvas animal paintings from 1995 the eyes of these creatures fuse with the viewer – a connection that makes the viewer consider the subject’s life force. The animals, however, are painted with a gentler colour application when compared to Cahn’s ‘Männer’ (Men). In the animal paintings, vibrant colours transition in strokes and flows that the viewer follows, as though petting the animals with their eyes.

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘Tier’, 1995, oil on canvas, 3 parts, various dimensions, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘Tier’, 1995, oil on canvas, 3 parts, various dimensions, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Existential themes emerge from the material undertones and overtones Cahn employs – especially in her nature paintings. Take, for example, her long portrait-format ‘Blumenfamilie in meinem Garten’ oil painting from 2017. Like Cahn’s animal paintings, the overall colour in the Blumenfamilie painting is more subdued than in her earlier colour works, while the precision of pigments used to compose its flowers delivers a powerful narrative.

The painting’s atmospheric, sea-foam green background transitions to a blue sky – a seemingly peaceful setting – while a quartet of glowing, yellow-faced flower Cyclopes stretch the length of the painting. A red underpainting that shadows the flowers’ thin, red stems interrupts the pacific green, and the stems pool in a bloody tangle of soilless roots at the bottom of the composition. The flowers seem uprooted, floating – the red representation of their vascular systems indicating danger and threat amidst an otherwise peaceful scene, not unlike the experience of refugees and displaced people.

A single eye painted in spirals of orange and red is present in the centre of each of the four flower heads in ‘Blumenfamilie in meinem Garten’. The singularity of their stares pierce the viewer, and the softness of the painting’s green, yellow and blue hues does not dampen the intensity of the work’s unblinking flower eyes and the secrets they are trying to tell us.

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘Blumenfamilie in meinem Garten’, 2017, oil on wood, 170 x 80 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Miriam Cahn (b. 1949), ‘Blumenfamilie in meinem Garten’, 2017, oil on wood, 170 x 80 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Eyes as a compass

Cahn’s recurring theme of intense eyes peering out from distinctive, haunting subjects is likewise seen

in her ‘Untitled’ oil painting from 2005, also in the Julius Baer Art Collection. In the foreground, a

ghost-like figure of a naked woman towers behind a child, both standing in a gauze of white. They are

exposed and seemingly lost in the landscape’s gorgeous strokes of purple, orange, and blue and its

stormy horizon, while the child at the painting’s base pulls the viewer’s eyes to their own like a

magnet – eyes that act as a compass, directing viewers to consider our shared humanity with those who

occupy liminal, marginalised stations in the world.

Throughout Cahn’s career, she has created subjects with probing stares that implore viewers to contemplate the experience of others and acknowledge the brutality and fragility of our mutual existence. Cahn’s messaging has not dampened through the decades; when seeing works that span her career in collections such as those housed with Julius Baer and in retrospectives like that at Palais de Tokyo, the power struggle communicated through her art’s intimate confrontations is amplified – a clarion call for viewers to bear witness to what, as Cahn calls it, is “the complexity of it all.”

Author: Jenny Magee