Pipilotti Rist: out of the bag

Portrait of Pipilotti Rist, photo: Gian Marco Castelberg

Portrait of Pipilotti Rist, photo: Gian Marco Castelberg

Pipilotti Rist’s playful, highly inventive and decidedly female take on video art and image-making technologies has made her one of the key global artists over the last 30 years. From today’s perspective, with images constantly surrounding us, the Swiss artist’s accessible, genre-defying and utterly joyous work feels visionary. This year Rist is set to receive the Kulturpreis des Kantons Zürich, one of Switzerland’s most prestigious cultural awards.

There was a time in the early 1990s when Swiss video artist Pipilotti Rist regularly used a rather cheeky description in her bio line – one that would come to be quoted liberally: ‘Her focus is video/audio installations’, the artist wrote of herself, ‘because there is room in them for everything (painting, technology, language, music, movement, lousy, flowing pictures, poetry, commotion, premonition of death, sex and friendliness) – like in a compact handbag.’ Years later, in an interview with curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Rist added that a handbag ‘contains the basics, but its contents are always a portrait of the owner. I love looking into other people’s handbags; they reveal their secrets and tell me a lot about their owners’ characters, about their wishes and fears. Exhibiting my art is like letting people take a look into my bag.’

Indeed, the handbag is a fitting image for the sprawling oeuvre and highly inventive work of this artist, who rose to fame during the 1990s as one of the era’s most defining visual practitioners. Rist was born in 1962 as Elisabeth Charlotte and adopted the name Pipilotti at least partially in homage to the childlike wildness and unlimited fantasy of Astrid Lindgren’s famous character Pippi Longstocking, who similarly paid little attention to boundaries and hierarchies. In Rist’s works, ‘high’ and ‘low’, pop music, fine arts, feminist body politics, technological know-how and immersive spatial installations all blend together to create a unique artistic vision that is at home on video screens, in exhibition spaces and in cinemas alike.

Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), ‘Edna’, 1995, from the series ‘Yoghurt On Skin – Velvet On TV’,

video installation with sound, 3 minutes 29 seconds, pillow and handbag, 110 x 40 x 40 cm,

courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2024, Pro Litteris, Zurich

Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), ‘Edna’, 1995, from the series ‘Yoghurt On Skin – Velvet On TV’,

video installation with sound, 3 minutes 29 seconds, pillow and handbag, 110 x 40 x 40 cm,

courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2024, Pro Litteris, Zurich

Handbags and shells

Take a canonical artwork from the mid-1990s that features actual handbags. For the 1994 installation

‘Yoghurt on Skin – Velvet on TV’, Rist presented several handbags and large tropical shells on elegant

poles, set in a room dimly lit in sensual reds. Each of these receptacles contains a small screen on a

short video loop. Open the bag and dive into another world – Pipilotti’s world, that is.

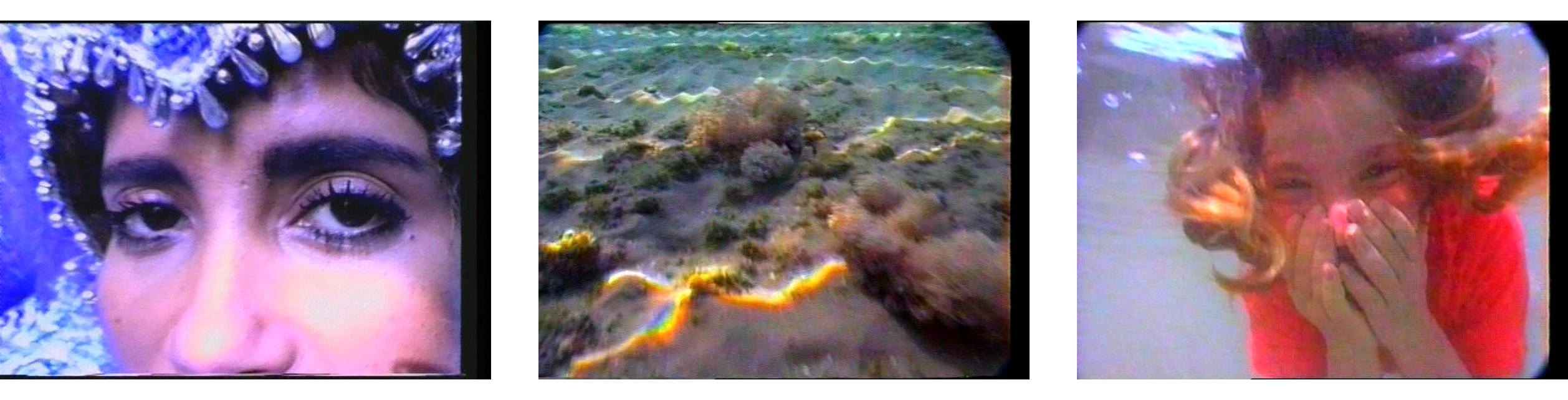

Fittingly, all the videos rely heavily on underwater footage shot in the Red Sea. ‘Edna’, for example, one of the handbag works in the series – and the first-ever video work to enter the Julius Baer Art Collection in 1995 – contains a video loop around three and a half minutes long. It’s the perfect length for a pop song, as they say. A soundtrack made up of quirky mashed-up music as well as what seems to be answering machine messages in different languages accompanies mostly aquatic imagery: a female head wearing a silvery cover on her head, reminiscent of fish scales; a kid happily dabbling and swashing in the ocean; a (slightly too) close shot of a swimming woman’s breast in a bikini; and, finally, blood running out of a woman’s mouth and down her body.

As if in a nutshell (or a handbag, for that matter) this work has it all: the quirkiness, the boundless oceanic feeling, the bright colours, the jumpy video editing, technical interference and ultra-close-ups resulting in slightly uncomfortable proximity, but also various fluids and the female body – as well as images of the latter and a subversive take on the uncanny gaze fixed upon it.

Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), three stills from the video ‘Edna’, 1995, from the series

‘Yoghurt On Skin – Velvet On TV’, video installation with sound, 3 minutes 29 seconds, pillow and handbag,

110 x 40 x 40 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2024, Pro Litteris, Zurich

Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), three stills from the video ‘Edna’, 1995, from the series

‘Yoghurt On Skin – Velvet On TV’, video installation with sound, 3 minutes 29 seconds, pillow and handbag,

110 x 40 x 40 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © 2024, Pro Litteris, Zurich

Body seen and body seeing

In general, the body, particularly the female body, and its relation to image-making technologies are

central to Rist’s oeuvre. Not only does Rist, especially in her early works, turn towards the framing of

the female body through the camera’s (traditionally male-centred) gaze, but in a highly inventive twist

she also establishes an analogy between the camera’s ‘eye’ and the human eye, thereby creating new

images that would be set against conventional ones. ‘Our eyes’, she once said in the 1990s, ‘are cameras

running on blood’. This approach goes hand in hand with an aesthetic of extreme close-ups that Rist has

cultivated over the years, often scanning bodies in such detail that the viewer has no idea what they

are seeing. It is a perspective that is simultaneously radically subjective and somewhat disorienting.

It leads to images that seem to break down the border between you and me, between a body seen and a body

seeing. To put it in other words, it embodies technological vision.

Works like ‘Yoghurt on Skin – Velvet on TV’ also stand at the threshold of Rist’s single-channel videos from the 1980s and early 1990s and her later, more expansive and ultimately immersive installations. Rist’s earlier works, like ‘I’m Not the Girl Who Misses Much’ from 1986 or ‘You Called Me Jacky’ from 1990, cheekily referenced pop songs and music videos, but stayed limited to conventional presentation modes on traditional screens. Now, though, she started to literally ‘embody’ her videos in sculptural settings – may it be a handbag, a shell, or, in other instances, a bathing suit – or projects moving images onto objects and interiors. Later, in works like ‘Sip my Ocean’ from 1996 or her canonical ‘Ever is Over All’ from 1997, which shows a young woman walking down the street smashing car windows with what seems to be a giant flower, she used the corners of the exhibition space to give her projections a spatial dimension so that they can ‘surround’ the viewers.

Immersion and utopia

After taking a break at the beginning of the new millennium when she went to California to teach, Rist

returned with several endeavours that included her first feature-length film ‘Pepperminta’ in 2009.

Within the exhibition space, meanwhile, the artist kept venturing further and further into the territory

of immersion, creating large-scale installations that featured cushions for the viewers and projections

on walls and ceilings with almost psychedelic imagery, combining everything from flowers and nature

shots to footage of body parts. These all-encompassing multimedia environments, for example, at MoMA in

New York in 2008/09, come close to Rist’s vision of the world – one that has neither hierarchies nor

unnecessary boundaries, seen as if through a child’s comparatively untainted eyes at the same time as it

is perfectly aware of all the obstacles, problems, and power relations that exist. It is a view of the

world that is inclusive and accessible and has the power to imagine things being different – and a

perspective that amidst today’s myriad political, societal and technological crises now seems more

needed than ever.

‘I am of the utmost opinion that human and cultural progress can only be achieved through positively formulated works’, Rist wrote in 1999. And so this is why she aims to use her energies ‘to (audio-visually) materialise utopias’. In that regard, Rist’s work exudes an almost fantastically utopian air, albeit one that results from hard work – however playful her works may come across. Hers is a utopia that is far from being a beautiful if somewhat detached vision; on the contrary, it is wrung from political realities, grounded in actual bodies, made of blood, flesh and water, and the images thereof. In creating imagery that, with its extreme close-ups and depictions of bodily fluids, is decidedly visceral, Rist’s works physically come very close – indeed, almost too close. And a whole world comes along with them. These images embrace us, and instead of looking at them stiffly we may respond to their embrace. A good hug needs (at least) two to make it work.

Author: Dominikus Müller