Raphael Hefti: Artist of our Industrial Age

Raphael Hefti in his studio in Zurich

Raphael Hefti in his studio in Zurich

Had you encountered Raphael Hefti this summer, leaning over anodising tanks at BWB-Betschart AG in the Swiss village Stans, you may have wondered whether the artist was lost in the factory. But Hefti opens up creative potential hidden within streamlined industrial processes and in so doing illuminates much about our society. We followed him to document his latest adventure.

Raphael Hefti feels at home in large-scale production facilities. Little wonder, for he first studied electrical engineering and industrial design before he segued into the prestigious photography course at Lausanne’s ECAL School and a Master’s degree at the Slade School of Art in London in 2013.

Even when still nominally a photographer – his practice has since spilled into other media – his work challenged archetypes: the ‘Lycopodium’ series from 2011-2015 is composed of photograms (one was acquired for the Julius Baer Art Collection in 2013), or images produced without a camera by directly exposing the photographic paper to light instead.

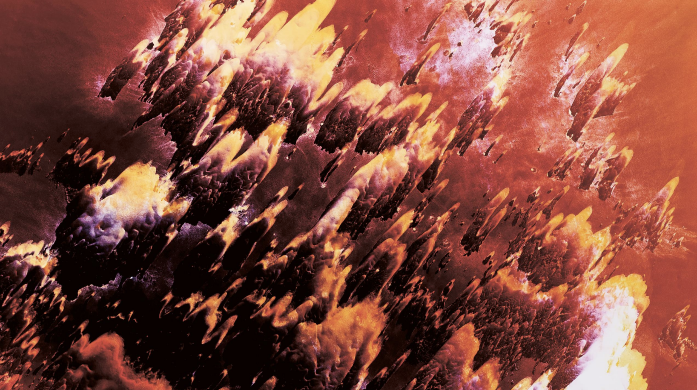

Raphael Hefti (b. 1978), Untitled (2011), from the series ,Lycopodium‘, photogram on photo paper, created by using the burning spores of the moss plant Lycopodium, detail, 164 x 105.5 cm.

Raphael Hefti (b. 1978), Untitled (2011), from the series ,Lycopodium‘, photogram on photo paper, created by using the burning spores of the moss plant Lycopodium, detail, 164 x 105.5 cm.

Hefti’s images were not created by masking areas of his vast banner of paper, but by burning lycopodium powder (the highly flammable dried spores of a fern) over long rolls of paper. Alongside its traditional uses, such as theatrical pyrotechnics and in homeopathy, lycopodium has even been employed to generate camera flashes. Turning a means of illumination into an image – a symbiotic relationship that photographers have long grappled with – Hefti also ‘exposes’ the Fujichrome paper itself, revealing the structure of the chemical fabric designed to capture colour. In the dark basement of his studio, the artist operated like an alchemist when art, science and technology were more closely wedded.

Go big or go home

Hefti’s recent projects are inevitably ambitious, often with a dose of the absurd: for

LIVE METALS in 2015, he

installed a CNC milling machine in his gallery’s Art Basel booth. The performance saw aluminium cylinders lathed

into a variety of shapes, echoing architectural and artistic precedents, ultimately disappearing as they were

carved away entirely.

In 2018, for We Are Not One Way Trip To Mars People (part of the exhibition ‘New Swiss Performance Now’), he covered the floor of Kunsthalle Basel with long stripes of the paint used for street markings. Recognisable from pedestrian crossings and traffic lanes, the material is here transformed into wild, mesmeric stripes; their colours intermingling to create an almost psychedelic effect. It formed a carpet the audience was drawn to walk along, staying in lane or straying sideways, breaking free from their environmental conditioning.

No man is an island

As you might imagine by this point, Raphael Hefti’s major works are not undertaken alone. The latter

performance involved around half a dozen people applying the paint: the artist himself, directing, alongside

studio assistants and street-marking professionals. Hefti’s collaborations are an improvised dance with partners

whose work normally demands uniformity and perfection.

Entering a factory setting that piques his curiosity, he gets to know complex processes through the technicians he meets and, importantly, learns what mistakes could occur and how he might exploit them. By “tickling [the experts] in the right spot,” as the artist puts it, Hefti invites the specialists to redefine and investigate the limits of the processes they have perfected over the course of years. Where the artist finds room for manoeuvre, his counterparts discover more about their own medium.

Creating the Julius Baer special edition

“Tickling experts in the right spot”– that is exactly what he manages to do at the BWB-Betschart factory in

Stans. BWB specialises in surface finishing treatments such as anodising for industrial applications, consumer

goods, aeroplanes or architectural finishes.

Anodising produces an oxide layer on the surface of a metal; an even, sterile, hardened and scratch-resistant surface that can also be coloured. But how does it work? A piece of aluminium or alloy is dipped in acid, rendering the surface porous at a microscopic level. At this stage it can be dipped in a colour – usually an even dye – before being resealed in hot water.

Hefti and his studio assistants disrupted this process to reveal compositions of colours not usually seen using this dyeing process. Using the porous metal as a canvas, he experiments with applying colours and washing them off. By doing so, he incorporates chance in a usually highly structured process, thus generating the kind of irregularity that is usually anathema in industrial manufacturing.

The outcome of his hard work are 500 unique artworks which 500 selected recipients of the publication ‘Surrounded by Art’ - one element of Julius Baer’s 130th anniversary celebrations this year – will receive as a special gift inside. Each one of the 500 half-millimetre-thick aluminium plates is unique, their colours applied by hand. Rather than striving for uniformity, Hefti sought individuality. The slight work is a lesson in individuality in the age of mass production.

Raphael Hefti’s new works, including large anodised paintings, are currently on show at his solo exhibition Salutary Failures at Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Gunnar Meier / Kunsthalle Basel.

Raphael Hefti’s new works, including large anodised paintings, are currently on show at his solo exhibition Salutary Failures at Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Gunnar Meier / Kunsthalle Basel.

Encountering the artist’s oeuvre invites us to consider the inherent aesthetics of the materials that surround us and the processes that transform them.

Author: Aoife Rosenmeyer