STILL WATERS RUN DEEP

Portrait of Roman Signer, photo: Stefan Rohner

Portrait of Roman Signer, photo: Stefan Rohner

Roman Signer is one of the key Swiss artists of the last fifty years. As someone who is interested in energy and force as much as the passing of time, Signer has developed his very own form of ‘time sculptures’ over the years. Kunsthaus Zürich is showing a selection of Signer’s works from the 1970s until the present day in a large solo exhibition from 4 April to 17 August 2025.

‘I spent my youth by the river’, Roman Signer recalls in an interview accompanying his show at Kunsthaus Zürich. Indeed, water as a humble but incredibly forceful element and as an epitome of constant flux and change never seems to have left the artist since he grew up right next to the River Sitter in the Swiss town of Appenzell in the 1940s and 50s. Water really feels like the perfect embodiment of Signer’s work as a quiet, seemingly light and makeshift feature that is nonetheless energetic and profound, occupying a unique and singular position within contemporary art.

As Signer said in another interview almost twenty years ago, his work ‘has always been to do with forces’ and is invariably ‘very elemental’. Above all, though, his art is concerned with transformation. A paradigmatic Signer piece is about releasing energy in an experimental set-up to observe and record its effects, and about rendering time visible by showing how things change between a ‘state a’ and a ‘state b’. The artist once summed up his approach in perfectly simple terms, utilising his characteristically subtle, deadpan humour: ‘In my work, something is always going to happen, is happening or has happened. Or could happen.’

For Signer, then, the essence of sculpture is what occurs to a given material or situation when a certain (natural) force is applied. The resulting artwork can either be an actual ‘thing’ in the exhibition space – as with the Zurich exhibition, which mainly focuses on Signer’s actual sculptures – or filmic or multi-part photographic documentation of an action or event. ‘Time sculptures’ is a term often used when referring to Signer’s work. ‘What fascinates me is that a force makes my sculpture’, Signer said in a video interview in 2023, ‘I just arrange things […] and then the sculpture is finished. Then, you could say, a force has manifested itself in the sculpture.’

Following this fascination, Signer has created a plethora of works since the 1970s. Indeed, the oldest piece in the Kunsthaus exhibition – the three-part photographic work ‘Bewegliche Elemente’ (Movable Parts) – dates back to 1971 and already shows the artist’s interest in movement and transformation. Over the decades that followed, Signer has realised most of his works outside in a natural environment, often set against a picturesque Swiss landscape with mountains high and rivers deep. Many of those works involve explosives to unleash energy and set things in motion. Signer has detonated countless little rockets, powering a wide variety of actions such as ripping the cap off his head; he has used detonation cords to trace beams of light in the cold winter night and make river water splash into the air for a few seconds like an impromptu fountain; and he burned down more than twenty kilometres of fuse over thirty-five days to symbolically connect his birthplace of Appenzell with St Gallen, the town where he currently lives.

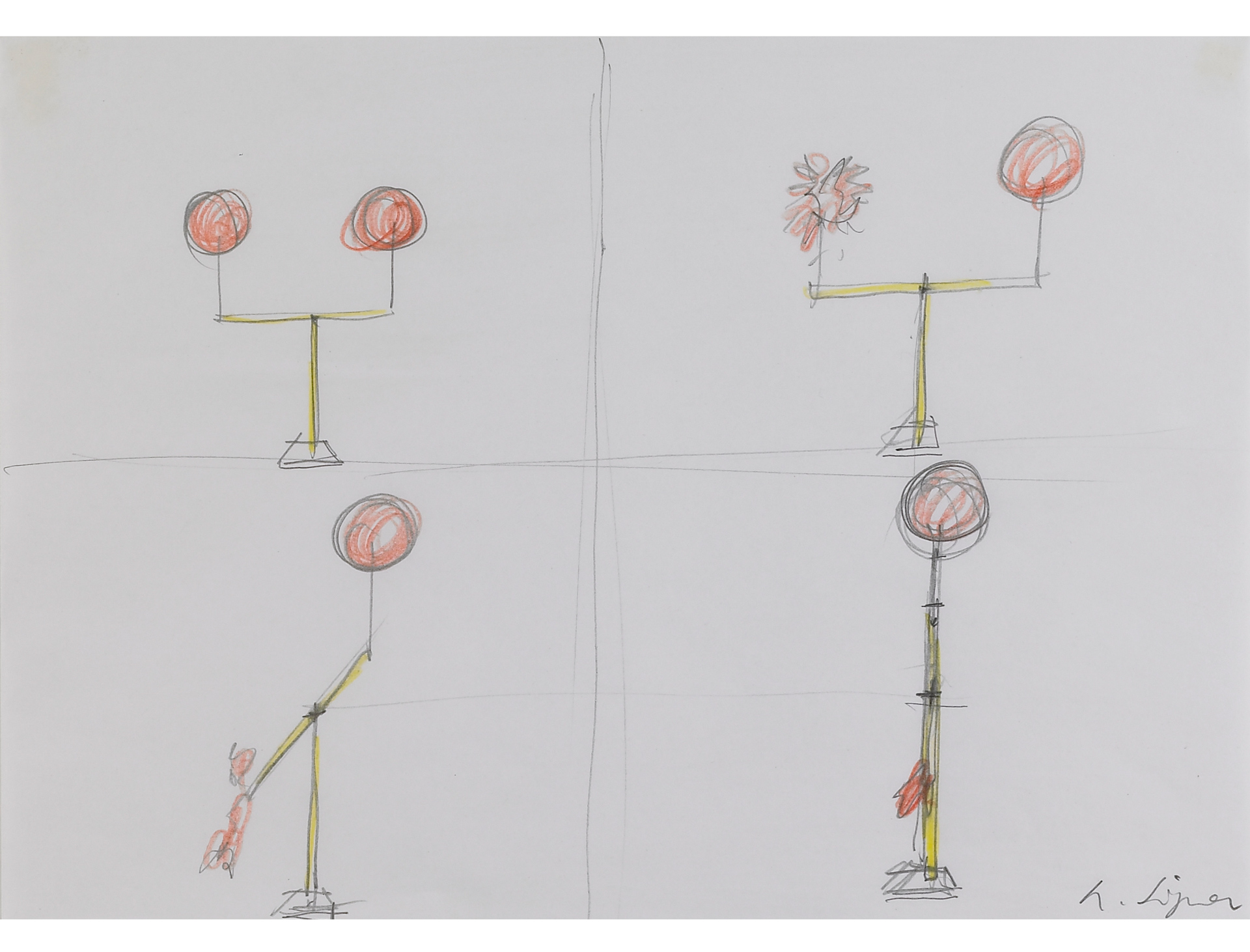

Given his use of explosives, Signer has sometimes jokingly been referred to as ‘the nation’s demolition expert’. But all explosives aside, his intention is far from destructive. Instead, the artist is seeking to visualise the chain of cause and effect. Just take a classic Signer work from 1983 in the Julius Baer Art Collection: the photographic series ‘Zwei Ballone’ (Two Balloons). The first plate shows the two eponymous helium-filled red balloons carefully held in equilibrium on a seesaw-like construction; balloons are among Signer’s simple signature props, alongside barrels, rubber boots and tables. The subsequent images document the explosion of one of the balloons and the seesaw shifting as a result. Even if the explosion is an integral part of the whole set-up, this is clearly less about destruction than about indicating that something ‘has happened’. Fittingly, the work feels a bit like an old-school signalling device.

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Zwei Ballone’, 1983, coloured pencil and pencil on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Zwei Ballone’, 1983, coloured pencil and pencil on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Zwei Ballone’, 1983, 3 parts, coloured photograph on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © Roman Signer

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Zwei Ballone’, 1983, 3 parts, coloured photograph on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © Roman Signer

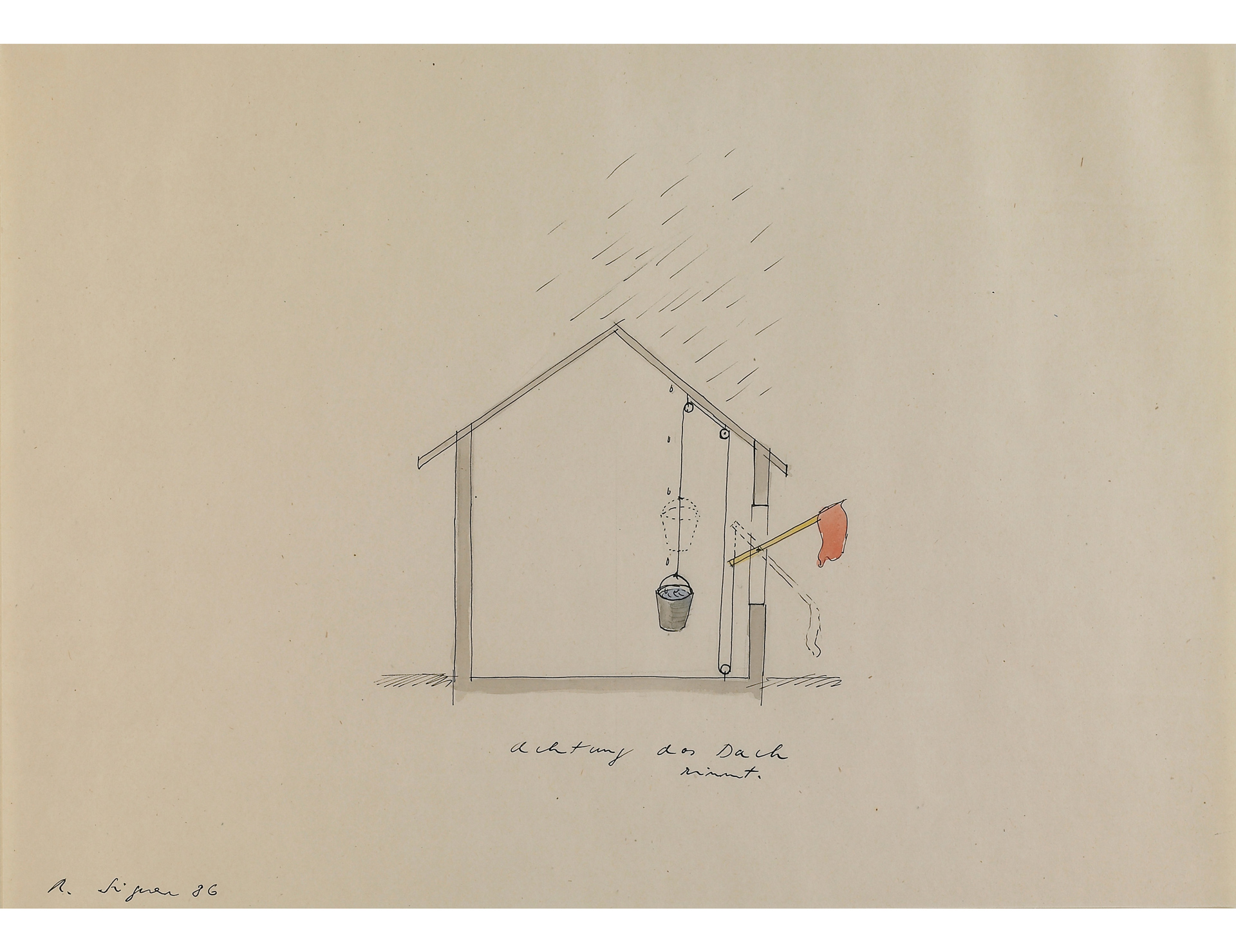

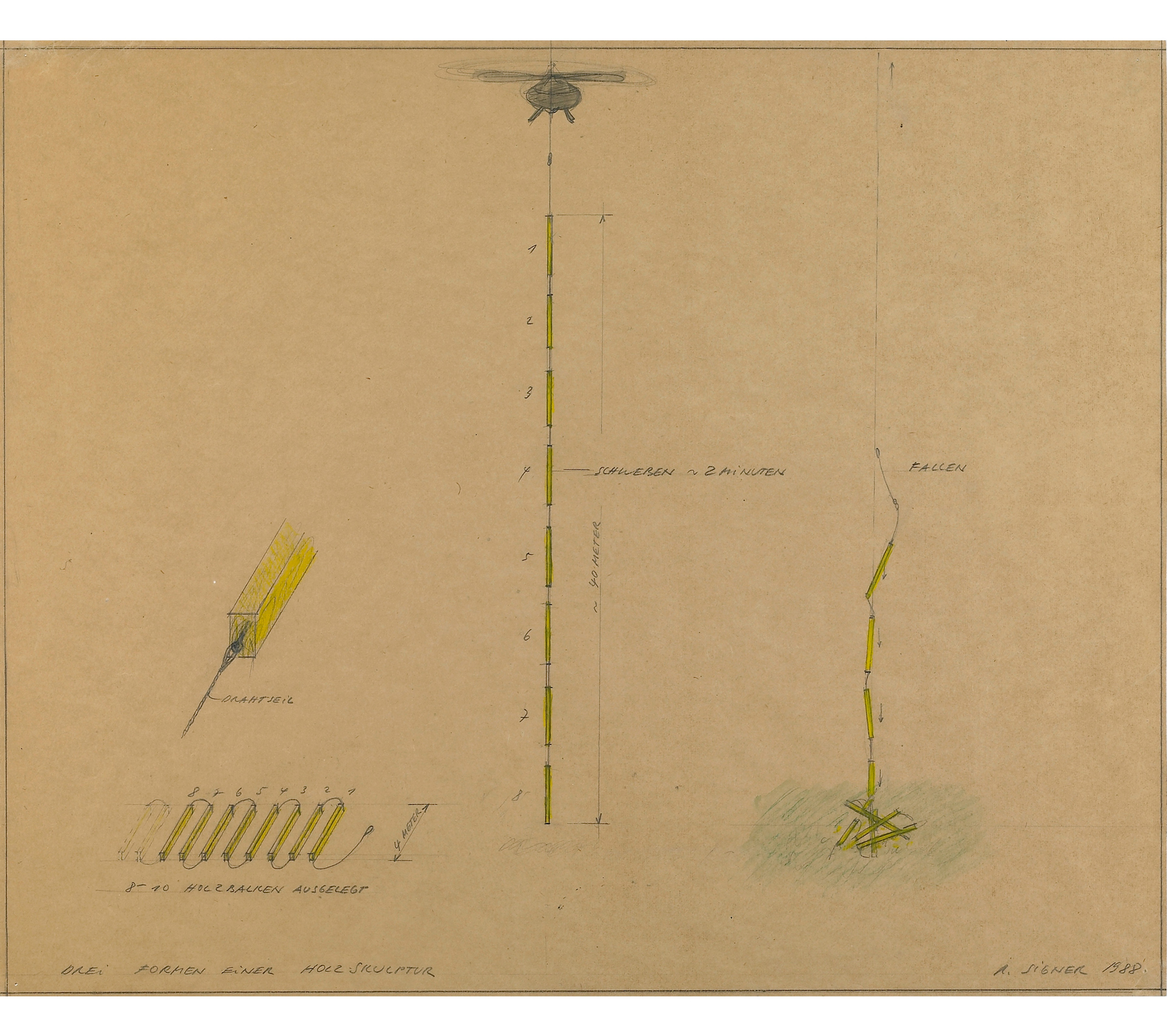

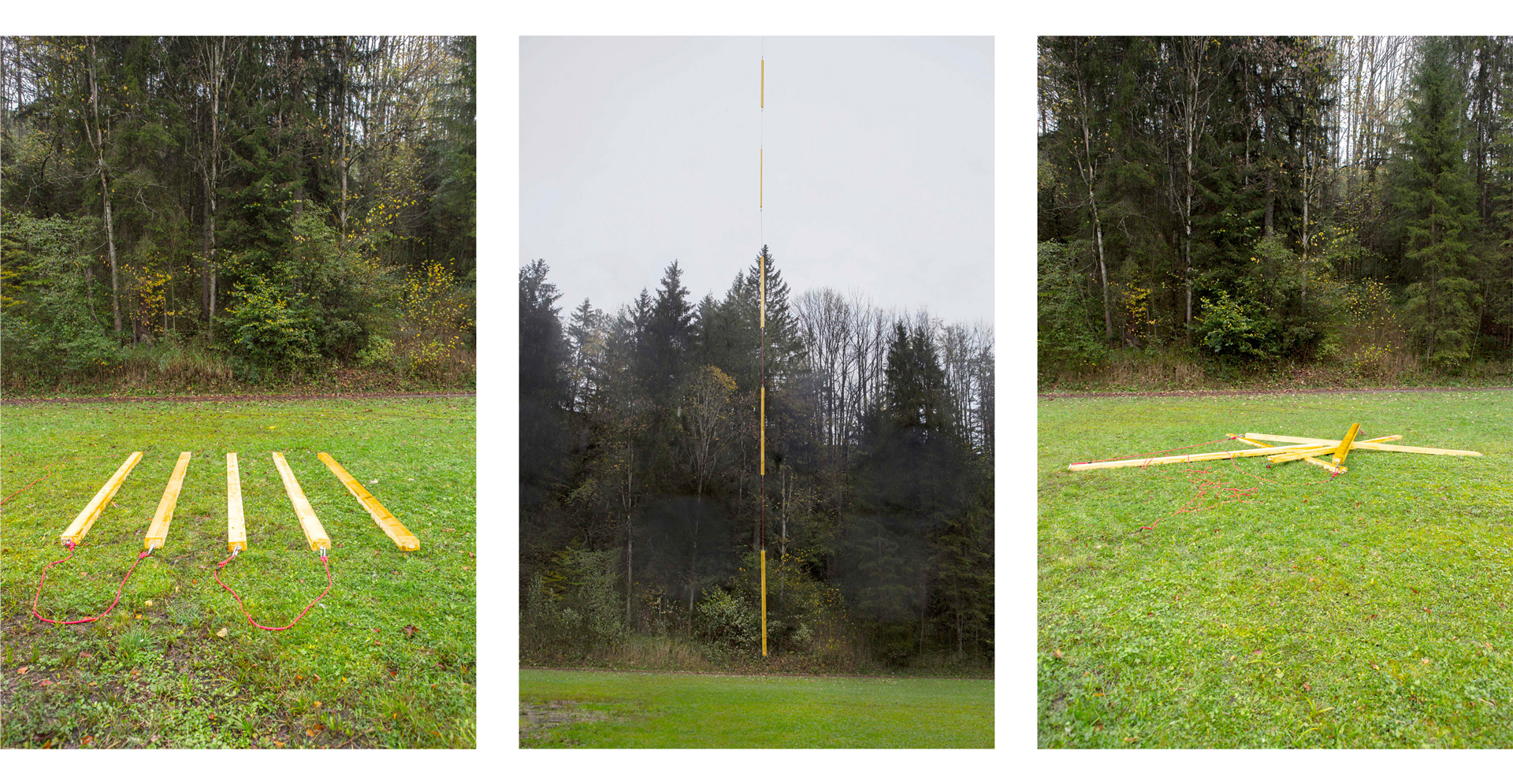

‘I always tried to find my own way’, Signer once said, ‘which cannot be quite straight.’ This rings true to his own artistic career as well. Born in 1938, Signer first trained as an architectural draughtsman in the 1950s, acquiring skills that are apparent in the painstakingly executed preparatory drawings he uses to sketch out actions and set-ups for his experimental works. Two examples of this are found in the Julius Baer Art Collection: the cheeky ‘Achtung, das Dach rinnt’ (Watch Out, The Roof is Leaking) from 1986, showing a house with a leaking roof and a bucket that collects water and connects to a red flag outside; and ‘Drei Formen einer Holzskulptur’ (Three Forms of a Wooden Sculpture), a work that Signer meticulously planned and sketched on paper in 1988 to be realised with support from Julius Baer in 2014, showing a set of connected wooden beams in three consecutive stages: firstly, arranged in a specific sequence, secondly, in the middle of an action – a helicopter lifting up the chain of beams – and thirdly, as a chaotic heap on the ground after the helicopter has released its freight and dropped it off.

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Achtung das Dach rinnt’, 1986, Indian ink and watercolour on paper, 30 x 42 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Achtung das Dach rinnt’, 1986, Indian ink and watercolour on paper, 30 x 42 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Drei Formen einer Holzskulptur’, 1988, pencil, coloured crayon and watercolour on wrapping paper, 50 x 61 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Drei Formen einer Holzskulptur’, 1988, pencil, coloured crayon and watercolour on wrapping paper, 50 x 61 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Drei Formen einer Holzskulptur’, 2014, 3 parts, photograph on polystyrene, 75 x 50 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © Roman Signer

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Drei Formen einer Holzskulptur’, 2014, 3 parts, photograph on polystyrene, 75 x 50 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, © Roman Signer

It wasn’t until the second half of the 1960s that Signer began to study art at the Schule für Gestaltung in Zurich and later at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Lucerne. In the early 1970s, he spent a year abroad at the Art Academy in Warsaw, studying in Oskar Hansen’s class. The time in Poland had a huge impact on Signer. Not only was it there – in a socialist country where scarcity dominated everyday life – that he discovered his characteristically sparse and humble use of material. During that time he also met his future wife Aleksandra, an artist in her own right, who would also go on to play a vital role in supporting her husband’s career by taking on the organisation and then filming, cutting and editing the footage documenting his actions.

Signer’s constant experimentation and steady work finally paid off in the mid-1990s, giving him the financial stability he needed to stop teaching on the side. In 1997, curator Kasper König invited Signer to the famous Skulptur Projekte Münster, an art festival in public space that is held in the German town of Münster just once a decade. Signer made quite a splash there, both literally and metaphorically, with two works: his ‘Spazierstock’ (Walking Cane, 1997) and his famous ‘Fontana di Piaggio’ (Piaggio Fountain, 1995), the latter now also parked in front of Kunsthaus Zürich as part of the current show. For this work, Signer turned a three-wheeled Piaggio Occasion vehicle into a mobile fountain. It is a typical Signer piece – beautifully poetic in its unpretentious simplicity, stunningly impressive in its makeshift inventiveness, and utterly sympathetic in its laconic and rather light-hearted approach. Two years later, the ‘Fontana’ was also part of the artist’s show in the Swiss pavilion at the Venice Biennale; alongside his Münster works, this marked Signer’s final breakthrough on the international stage.

The large-scale work that Signer developed for the pavilion itself saw him hang a dense grid of cast iron shots from the ceiling, only to release them in a carefully organised detonation; a video documentation of this piece is also part of the Julius Baer Art Collection. Each of the shots landed in a separate block of still-wet clay, resulting in a series of variations on a theme, namely the impact of the fall’s energy reflected in the clay. A work like ‘Eimer’ (Buckets, 2002) in the Julius Baer Art Collection follows a similar approach, only this time consisting of a series of photographs. For this piece, Signer hung twenty buckets full of water from the ceiling in a rectangular grid, then positioned himself centrally beneath them and released the detonation. The bucket fell and hit the ground, resulting in a reverse movement of the liquid splashing up (another one of Signer’s signature moves) and ultimately creating a wall of water around the artist.

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Eimer’, 2002, 6 parts, video print in colour, 29 x 21.5 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, video print: Aleksandra Signer, © Roman Signer

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Eimer’, 2002, 6 parts, video print in colour, 29 x 21.5 cm each, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection, video print: Aleksandra Signer, © Roman Signer

Change, transformation and movement as an indicator of energy also find their expression in Signer’s repeated usage of vehicles: not just the Piaggio car mentioned above but also bikes and skis (after all, we are in Switzerland!), and even model helicopters or, more recently, drones. But it is kayaks that occupy a very special place in his work. Since a fourteen-year-old Signer first saw two people paddling down the River Sitter in kayaks, he has been fascinated by these simple, elegant yet swift vessels. Over the years, they have appeared in many of his works – sometimes as full-on ready-mades and sometimes cut into pieces, as with ‘Kajak, orange/weiss’, for example, an early sculptural work from 1987 in the Julius Baer Art Collection, or the 1988 ‘Kajak I’, which is on view in the Kunsthaus exhibition.

In one of Signer’s most iconic works, we see the artist sitting in a kayak and paddling – not on the river itself but being dragged behind a car on a dirt road running next to it, ‘riding’ the boat until its bottom is ripped open. In a completely unplanned aspect of the video, a bunch of cows frantically gallop alongside the artist. It is a perfect Signer work, at once somehow serenely violent, testing the material’s limits, yet open and humorous. ‘I like the lightness’, the artist once said. ‘My sculptures always had a sense of lightness.’

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Kajak, orange/weiss’, 1987, kayak made of polyester with cut off bow and stern (3 parts), 40 x 400 x 60 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Roman Signer (b. 1938), ‘Kajak, orange/weiss’, 1987, kayak made of polyester with cut off bow and stern (3 parts), 40 x 400 x 60 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Ultimately, it is this very lightness, often resulting in an air of melancholy, that feels even more unique these days in an increasingly complicated and tightly regulated world. The unpretentious directness and seemingly improvised precarity of Signer’s work feel as if they come from a different age, when it was still possible (albeit not always allowed) to light a rocket in an empty riverbed somewhere in the Swiss countryside. Indeed, much has changed over the last fifty years, and much water has run down the River Sitter. Switzerland is an altogether different country now, and so is every other country in the world. Yet Signer’s work seems to be okay with that. It wasn’t really about holding on to things anyway. ‘The river’, Signer fittingly says in the catalogue to his show at the Kunsthaus, ‘carries thoughts onwards. It runs from one city into another, into another country, into fantasy.’

Author: Dominikus Müller

Don’t miss the exhibition ‘Roman Signer: Landschaft’ at Kunsthaus Zürich until 17 August 2025.