Sylvie Fleury: Tailoring Objects of Desire

Sylvie Fleury in her studio, photo: Diego Sanchez, 2022

Sylvie Fleury in her studio, photo: Diego Sanchez, 2022

In ‘Colorful 5 (Gold and Blue)’, a 2018 painting from Swiss artist Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), a lineup of four bands – each of which has a blue undertone – progresses from light to dark in quarter turns, punctuated with a contrasting gold-hued strip at the far right of the work, and all encased in black trim on its large, pill-shaped canvas. The form of this work is reminiscent of Frank Stella’s shaped canvases, which are significant and unique compositions in themselves rather than standardised supports that merely make compositions possible. Fleury is known for her barbed appropriations of modern art’s visual shorthands – especially those imposed by the male-dominated canon of art history – and ‘Colorful 5 (Gold and Blue)’, one of four works by the artist in the Julius Baer Art Collection, is no exception.

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), ‘Colorful 5 (Gold and Blue)’, 2018, acrylic on shaped canvas, 101.5 x 156.5 x 6.7 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), ‘Colorful 5 (Gold and Blue)’, 2018, acrylic on shaped canvas, 101.5 x 156.5 x 6.7 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

High style is Fleury’s artistic currency, and she is unafraid to sample commodified, clichéd styles from glorified male artists and tailor them with stitches of humour, feminism, sex and contemporary consumerism, as she does with ‘Colorful 5 (Gold and Blue)’, a painting that renders an eyeshadow compact some twenty times larger than the cosmetic’s standard size. The optical transformation is more than mere abstraction, as the painting triggers viewers to consider the commonalities between the arts and the routine vanity imposed upon women: pigments, emulsifiers, primers, tools, methods, palettes and the fads of seasonal, disposable fashions – all of these elements, and more, that are mixed to elicit desire.

Part of Fleury’s artistic magic is that looking at her work is like gazing into a prism of philosophical ideas expressed through shared visual languages while referring to the hackneyed ideas of gender in a playfully humorous way.

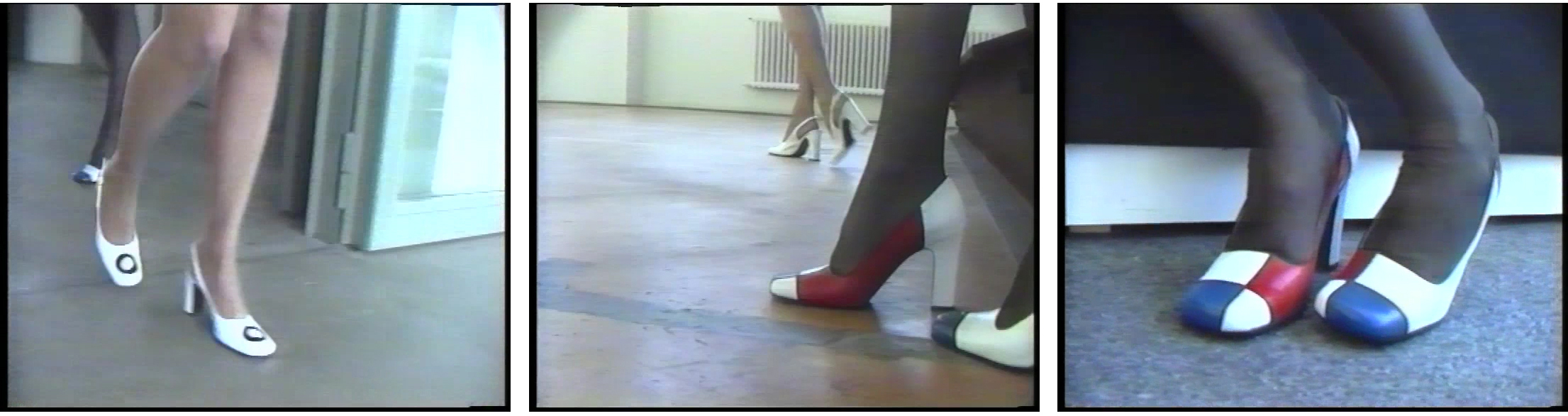

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), stills from the video ‘Walking in the museum’, 1997, video with sound, loop, duration: 24 minutes and 5 seconds, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), stills from the video ‘Walking in the museum’, 1997, video with sound, loop, duration: 24 minutes and 5 seconds, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Vagaries of style

Take, for example, Fleury’s 1997 video ‘Walking in the museum’, another work in the Julius Baer Art

Collection. A camera follows a woman in a pair of colour-blocked high-heels by British–Canadian designer

Patrick Cox – shoes that appear to be made out of a skinned Mondrian canvas – as they navigate an art

collection. The shoes in this setting plants a Mondrian seed in the viewer’s mind, which in turn recalls

the Dutch artist’s 1971 essay ‘Dialogue on Neoplasticism’, where he writes that “the ideal is

plastically manifested aesthetically as beauty”.

The shoes and the museum represent objects of attraction, expressing the tension and humour between the practical and the luxus, the collector and the collected, and the vagaries of style and the commodification of an art history dominated by male artists. Fleury brings forth these ideas that are found in both high fashion and canonised art, examining how consumer fetishes are fuelled by the sense of power gained from attaining status symbols, goods designed to be exclusive and out of reach, making them all the more desirable.

Fleury, a multimedia artist from Geneva, Switzerland, has always been drawn to what she calls “the mechanisms of desire – how objects elicit desire, and how brands create that sense of longing. These were things that felt really new when I started working in the 90s, when consumerism was really accelerating.”

After finishing her schooling in Geneva, Fleury went to New York City and got involved with the art scene while taking classes at the Germain School of Photography in Manhattan. When she returned to her home city, she continued to train independently and developed a refined artistic vocabulary that she translates into sculpture, painting, neon, photography, film and performance in order to explore the magnetic properties of consumption, especially the consumption of luxury goods marketed at women.

Readymade brand recognition

As an artist, Fleury has always questioned the value of luxury objects while transforming them into

readymades in the tradition of Marcel Duchamp, in which objects are reconsidered as art in new contexts.

But instead of Duchamp’s bicycle wheels and bottle racks, Fleury has chosen to recontextualise luxus

items and beauty products and remodel them into art throughout her vast and varied career.

It was in 1990 that Fleury first showed ‘Shopping Bags’ – a readymade work for the modern consumer age – in Jacqueline Rivolta’s exhibition space in Lausanne, Switzerland. The ‘Shopping Bags’ installation draws out the power of superficial appearances, particularly inasmuch as they relate to status and brand recognition.

What does the desire inspired by such packaging say about us? And once the high of a purchase has come and gone, what does the urge for another portion signal? Using neon, a medium with a romantic past in advertising, Fleury spells out one answer: ‘Égoïste’, a person overly concerned with their desires, needs or interests. But, like so much of Fleury’s oeuvre, ‘Égoïste’ (also housed in the Julius Baer Art Collection) contains a multitude of layered meanings.

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), ‘Égoïste’, 2000, white neon, 8.8 x 50.8 x 3.1 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), ‘Égoïste’, 2000, white neon, 8.8 x 50.8 x 3.1 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

The work, made in 2000, belongs to a series in which Fleury transferred the names of luxury perfumes into light sculptures. In essence, it is a readymade composed with a brand name, reformed and recontextualised. It allows viewers to reassess their relationship with branding by removing an object and leaving just its trademarked title. This concept literally illumines how brand values offer identities that are attainable through wealth’s commercial agency. However, this identity, like perfume, is in a constant state of degradation that fades after an item is purchased and utilised unless more resources are routinely applied and replaced.

Extrapolating the root sources of consumer desire is a hallmark of Fleury’s decades-long career, an overview of which can be seen at Kunst Museum Winterthur until 20 August 2023 in an exhibition titled ‘Shoplifters from Venus’. This major exhibition, which the museum describes as “an insight into the diverse and consistently developed oeuvre of one of the country’s most important artists”, is one of many highly regarded tributes to Fleury’s contributions to the arts in recent times. These honours include receiving the Swiss Grand Award for Art/Prix Meret Oppenheim in 2018 and France’s Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres Award in 2020.

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), ‘Cuddly Painting’, 1991, synthetic fur on wooden stretcher, 40 x 40 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Sylvie Fleury (b. 1961), ‘Cuddly Painting’, 1991, synthetic fur on wooden stretcher, 40 x 40 cm, courtesy the artist and Julius Baer Art Collection

Sensory seduction and forbiddance

Surfaces and materials are thematic in Fleury’s oeuvre. Along with her films of sleek, chrome-detailed

cars pumping their hydraulics as they smash cosmetics below their tyres – producing an explosion of

colour rather than Pollock-like scattered pigment drips – Fleury has created numerous works that beg

viewers to touch them while simultaneously restricting that urge.

As a case in point: Fleury’s ‘Cuddly Painting’, 1991, is another work in the Julius Baer Art Collection. This 40-cm square of synthetic fur entices the viewer to pet its shiny, long hairs, but as an artwork it remains inaccessible, forbidden from being touched by anyone but the artist or owner. It seduces the viewer with its sensory power while simultaneously rejecting them – like so much art, it’s made to be seen but not touched.

In an interview for Fleury’s 2017 exhibition of her Eye Shadow works at Salon 94 in New York City, the artist explained: “I’ve worked with this theme of seduction in previous artworks. [In] my first solo show ever, the walls were covered with little monochromes that I made by stretching fake fur on them. I called them ‘Cuddly Paintings’. There is this notion of desire and the forbidden and guilt.”

Accessible unattainability is threaded through much of Fleury’s art: a body of work that deconstructs and repackages the systematic mechanisms of seduction and desire. Fleury’s art doesn’t tell us not to want things – it makes viewers contemplate why.

Author: Jennifer Magee